On March 12, 1832, La Sylphide premiered at the Paris Opera, starring the choreographer’s daughter, in the role of the sylph. Wearing small wings on her back and a gauzy skirt that covered her knees but revealed her ankles and feet, Marie Taglioni created a unique image of ballet. She danced for a sustained length of time on the tips of her toes – on pointe.

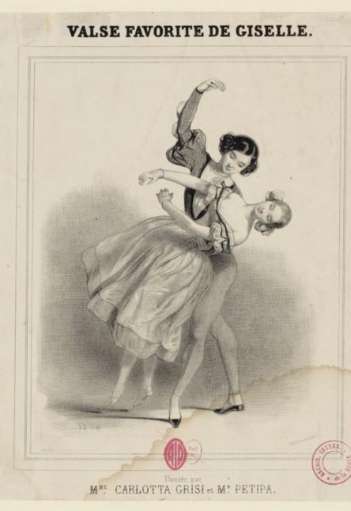

Giselle, which opened in 1841 in Paris with choreography by Jean Coralli and Jules Perrot, inverts the trope of La Sylphide. Using Heinrich Heine’s description of the Wilis in his anti-Romantic book De l’Allemagne and a verse poem by Victor Hugo, the ballet tells of a young village girl, Giselle, wooed by a disguised nobleman, betrothed to the daughter of a Duke. When Albrecht’s deception is revealed Giselle goes mad, dancing until she falls and dies in her lover’s arms. A remorseful Albrecht brings flowers to Giselle’s grave, where he is confronted by the Wilis, spirits of women who have died abandoned by their lovers. The Wilis insist he dance until his death, but he is saved by Giselle’s love.

Again the love triangle, male unfaithfulness and a second act full of beautiful ethereal women in gauzy white skirts, floating in regimental order – but this time enacting revenge – take centre stage. The ballet has an added post-Revolution nuance: the faithless male is a nobleman. Lucien Petipa would dance the role of Albrecht. And his brother Marius would revive the ballet for the Imperial Theatre in St. Petersburg.

Some years later, as ballet master of the Imperial Theatre, Marius Petipa choreographed three of the ballets that dominate today’s classical repertoire: Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker. These ballets harken back to the exquisitely feminine otherworld defined by La Sylphide. Significantly, all three ballets were set to music by Tchaikovsky, who worked to his ballet masters’ specifications, but whose genius for writing ballet music has only been surpassed in the twentieth century by Igor Stravinsky.

Swan Lake was Tchaikovsky’s first ballet, written for the 1877 première with choreography by Julius Reisinger, the ballet master at the Bolshoi Theatre. Badly received, it continued in the repertoire for six years. Tchaikovsky intended to revise the libretto and score for Petipa, but died, leaving the revision to Riccardo Drigo and his brother Modest Tchaikovsky. Petipa, who was ill, shared the choreography with Lev Ivanov. What they changed, primarily, was the ending. Rather than the grim tempest and death of the Swan Queen betrayed unwittingly by her Prince, love lifts both the Swan and the Prince into an apotheosis – a transfiguration beyond death.

The second act is again filled with ethereal gauzy white, the sylph’s wings have become the swan maidens’ feathery arms. Victims of evil rather than faithlessness, they have been transformed into swans and only resume their true shape at night. This central image is bookended by court scenes, where the narrative is often delivered through mime rather than dance. Petipa’s interests were courtly rather than revolutionary, and he strove to maintain ballet’s roots in the sixteenth-century French court, as an embodiment of the glory of the monarchy. The corps de ballet’s stylized and orderly formations expressed the formal etiquette of aristocratic hierarchy. Almost all revivals of those ballets have been based on Petipa’s demanding choreography made exquisitely precise by later choreographers.

Revolution came in the late twentieth century, first with Mats Ek radically contemporary take on Swan Lake (1987) then Matthew Bourne’s 1995 reworking of the story into a satirical portrayal of monarchy, with a Prince whose oedipal and homoerotic longings drive him to madness and illusory visions of dancing swans. The corps de ballet and the Swan are all male, and the Black Swan makes his appearance at court in black leather pants and wielding a riding crop. Bourne’s choreography is vividly masculine, feral and dynamic in its energy. But even in Bourne’s Swan Lake the swans signal an imaginary world, something beyond the comic reality of everyday life. A dream world of the soul split from its own fulfilment.

Created for The Royal Ballet in 2013, Wayne McGregor’s Raven Girl, conceived in collaboration with contemporary writer and visual artist Audrey Niffenegger, resonates with choreographers’ interpretations of Swan Lake, and the ballet’s very concept of the Swan. A postman falls in love with a raven and their love child is half raven–half human. She comes across a Doctor who agrees to perform surgery to give her wings. Mutilated, but still unable to fly, she is torn between both halves of her identity. Her internal conflicts pull her, finally, away from the human world and into the soaring, glittering world of the Raven, as a Raven prince falls in love with her.

Mark Morris revised The Nutcracker in his satiric version The Hard Nut, which premiered in 1991. Using the comic book graphics of Charles Burns to reinforce the darker side of Hoffmann’s childhood, the ballet is set in post-WW2 America and filled with gender-bending appropriations of the Petipa ballet. The corps de ballet of snowflakes features both male and female dancers on pointe. The family’s maid is a travesty role, and is also danced on pointe.

Moving away from the Romantic fantasy that was essential to ballet, the storybook ballet continues to challenge choreographers. Ballet’s ability to open a window into a world of the imagination and present an idealized mythology was central to the nineteenth-century story ballets that remain the foundation of ballet’s identity – Giselle, Sleeping Beauty, Swan Lake, Coppélia, The Nutcracker. But their idealizations linger in even the most abstract and formalistic ballets of the twenty-first century. They are built into the ballet dancer’s body and technique. These are the bodies we would be – strong, athletic and graceful, moving to emotionally vibrant music and telling our stories of sorrow and joy. Looking through the proscenium arch we see a distant enviable world where gravity seems suspended, and all is exquisitely charged with meaningful love.