This article was updated in December 2024.

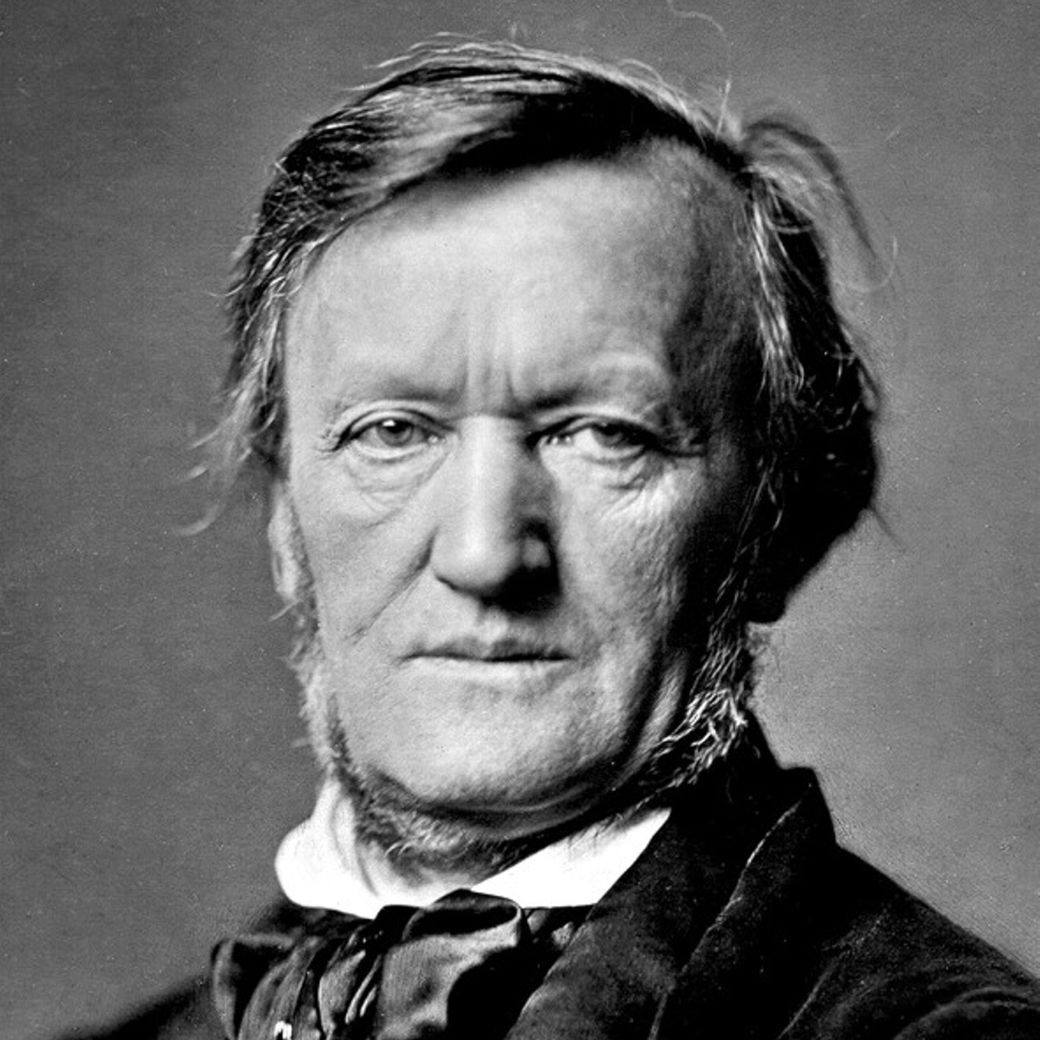

It’s early morning on 23rd December 1857, and the bittersweet strains of a chamber ensemble performing a passionate Lieder arrangement waft through the villa on Zurich’s “green hill” – a beautiful way to waken the lady of the house on the morning of her 29th birthday. The romantic gesture was initiated by Richard Wagner, and the song being performed is his recently-composed Träume. But the lady just waking up isn’t his wife – she’s preparing the breakfast – it’s the wife of his patron, a muse and the current object of his affections.

Wagner ended up in Zurich after having to flee Germany due to his inflammatory activities in the Dresden Uprising of 1849. There, he kept up his musical activities, giving a concert at the city’s Aktientheater in April 1853 where a silk merchant and his poet wife were in attendance. Otto and Mathilde Wesendonck had married five years before and were living in the local Hotel Baur au Lac while their new mansion was being built. It was through staying at this establishment that they came to know the fiery composer and his wife Minna. The two couples hit it off: the Wesendoncks were in thrall to Wagner’s music and sympathised with his republican tendencies. But there was another dimension to the relationship. “A rich young merchant, Wesendonck… settled down at Zurich some time ago and in great luxury,” wrote Wagner to a friend. “His wife is very pretty and seems to have caught some enthusiasm for me.” When Otto began funding Wagner’s musical pursuits, the composer wrote his Piano Sonata in A flat major in honour of the merchant’s wife. In 1857, when the Wesendonck’s villa was finally built, Otto rented a cottage on the grounds to the Wagners at friend’s rates – rates which Richard only occasionally deigned to pay.

When Otto was away, Wagner had the run of the villa and used it to throw parties and house friends for long periods of time. Meanwhile, the creative funk that had dogged the composer since the completion of Lohengrin in 1848 finally began to thaw, and he recommenced work on his latest opera, Tristan und Isolde, in the autumn of 1857. The love triangle that was developing between himself, Minna and Mathilde could only have been fuel to his creative fire. The soulful and literary Mathilde even provided practical assistance in the composition, Wagner reading her a new part of the libretto every day. At the same time, they were also working together on a new series of songs. Mathilde wrote a set of five poems and, as she completed each one, Wagner began setting them to music, a process which the poet described as a “supreme transfiguration and consecration” of her words. The music, moreover, was closely bound up with the nebulous score for Tristan, particularly in the third and fifth songs in the series, Im Treibhaus” and “Träume, elements of which would make their way into the Prelude to act three of the opera. Der Engel, on the other hand, draws from a moment in Das Rheingold.

The collection that the pair eventually produced was a set of five songs, originally titled Fünf Gedichte für eine Frauenstimme (Five Poems for a Female Voice), though now known as the Wesendonck-Lieder. With a Schopenhauerian sense of fatality in Mathilde’s words, coupled with the conflicted yearning of Wagner’s music, one gets a strong sense of the emotionally fraught atmosphere in the Wesendonck mansion at the time. In Stehe Still, for example, Mathilde writes of “Glowing spheres in distant space / Circling us with gravity”, calling for “All sempiternal generation” to cease, while Wagner provides worrisome instrumental accompaniment. The austere Schmerzen, meanwhile, oscillates between despair and optimism, ending in a triumphant climax in which the singer submits to the dual nature of existence: “If death alone gives birth to life / And only torment can bring joy / How grateful am I for such torment / As Nature does in me deploy.” Finally, the fatalism of Schmerzen gives way to the idealism of Träume, in which Wesendonck retreats inward to the mind for succour, accompanied by Wagner’s gentlest music in the cycle – orchestrated for an ensemble rather than just piano and voice.

Things fall apart

When Wagner arranged the Träume performance for the morning of Mathilde’s birthday, Otto was seeing to business matters in New York. Wagner had paid for the chamber ensemble that played the music using Otto’s money, and when his patron returned he was understandably upset. Wagner arranged for another concert performance in the villa to placate the businessman – this time movements from Beethoven's symphonies were played – but by now the relationship had soured. A scenario summing up the strange atmosphere in the house could be an evening in September of that year when the conductor Hans von Bülow came to visit with his new wife Cosima (who was Liszt’s illegitimate daughter). That evening, Wagner read the party his Tristan libretto, and the audience included his wife Minna, his current romantic interest Mathilde, and Cosima, with whom he would later have two children while she was still married to von Bülow.

Things came crashing down in April the next year when Minna got hold of a letter that Wagner had sent to Mathilde, in which he praised her as an angel and declared his profound love for her. Minna confronted her love rival with the letter and also showed it to her husband, after which the Wagners decided to leave. Richard went to Venice, Minna to Dresden to recover her nerves. Their relationship never recovered, with Richard not even attending the funeral when Minna died in 1866. Before leaving Zurich she had written a caustic letter to Mathilde, saying, “I must tell you with a bleeding heart that you have succeeded in separating my husband from me after nearly twenty-two years of marriage,” and in a subsequent letter to her husband she referred to the poet as “that filthy woman”. Almost incredibly, however, the relationship between Richard and Otto endured, the merchant contributing to the composer’s Bayreuth festival project (though, when Wagner asked to be allowed to stay at Otto’s cottage again a few years later, his request was declined).

The Wesendonck-Lieder cycle was later orchestrated by the Austrian conductor Felix Mottl. Originally written for female voice, they came to be interpreted by tenors through the 20th century (read our chat about the songs with tenor Stuart Skelton here). While they were still in touch, Wagner wrote to Mathilde of their lieder series: “I have not written anything better than these songs and very few of my works will be remembered besides them.” While history has proved him wrong, the Wesendonck-Lieder stand out as an absorbing document of Wagner’s complex relationships, revealing the composer in his most fragile mode.

Find forthcoming performances of the Wesendonck-Lieder here.