This article was updated in September 2025.

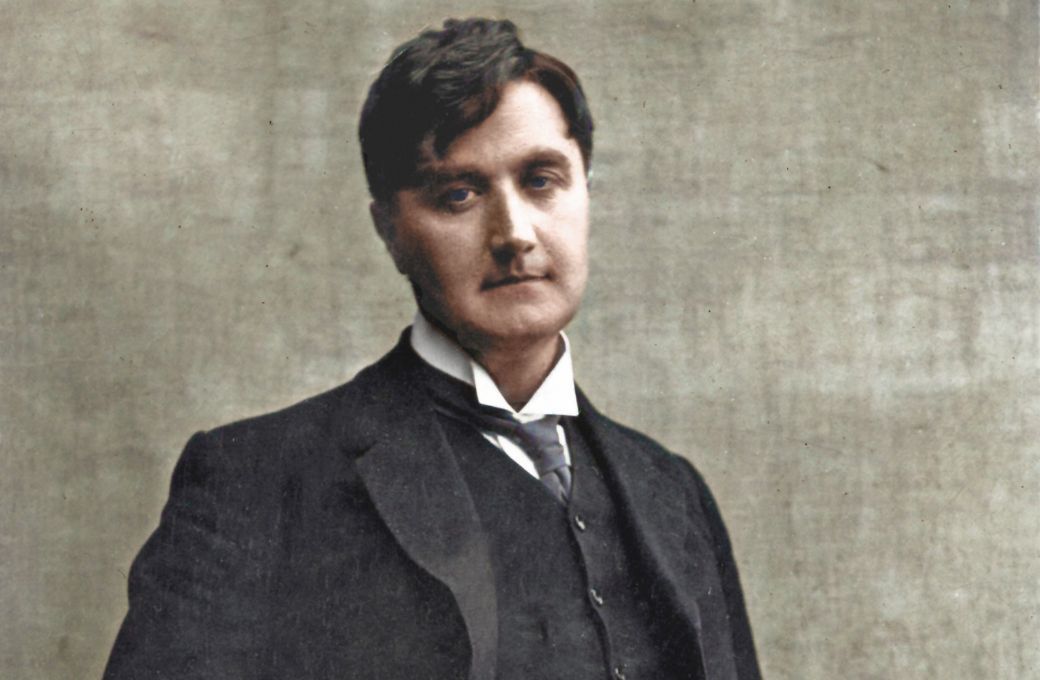

There are some pieces of music where you can remember the exact circumstances under which you first encountered them. Most of my discoveries were via disc or the radio, but not so the Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis by Ralph Vaughan Williams. It opened a concert in Winchester Cathedral by the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra under Richard Hickox. I didn’t know a note and it simply bowled me over. On reflection, the cathedral setting – far from ideal for most classical music – was perhaps the best environment to hear the Tallis Fantasia for it was premiered in one, Gloucester Cathedral.

Vaughan Williams wrote the work for the Three Choirs Festival in 1910, where it was first performed under the composer’s baton by the strings of the London Symphony Orchestra. It was the curtain-raiser for Sir Edward Elgar, who then conducted his choral masterpiece The Dream of Gerontius. Elgar’s response to the new composition was not, as far as I am aware, recorded, but we do know that the premiere knocked the socks off two of the cathedral’s young organ scholars, future composers Herbert Howells and Ivor Gurney, who wandered the streets of Gloucester for hours afterwards, transfixed by what they had heard. Years later, Howells reminisced, “For a music-bewildered youth of 17, it was an overwhelming evening, so disturbing and moving that I even asked RVW for his autograph – and got it!”

So what is it about the Tallis Fantasia that so moves me? Why is it one of RVW’s best-loved works, second only in popularity to The Lark Ascending in the wider public consciousness? Perhaps, like The Lark, there’s an element of what the sceptics like to dismiss as a tweedy nostalgia to it, rooted in the past, an idyllic image of pre-war England, of tea and crumpets, cathedral choirs and cricket on the village green. But that would be to do the work a disservice for it has a melancholy atmosphere, a gravitas that isn’t nostalgic, but is timeless. Indeed, time seems to stand still in the work’s five haunting opening chords.

The very first chord is ethereal – a G major chord spread really wide from a low (contra) G right to the top of the treble staff that seems to float in space. Vaughan Williams moves to A flat major, then to G flat and then the violins sustain a long, high D, under which the lower strings first pluck, then bow hints of the main theme on which the work is based. This theme is a Tudor tune by Thomas Tallis that Vaughan Williams discovered when he was editing The English Hymnal, a psalm chant written for the 1567 Psalter of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Matthew Parker.

It had rousing words for Protestant England: “Why fumeth in sight: The Gentils spite, In fury raging stout? Why taketh in hond: the people fond, Vayne things to bring about?” Yet Tallis’ tune is written in the Phrygian mode, one of the least common musical scales, in which many of the intervals – the second, third, sixth and seventh – are flattened, so the music sounds unusually dark.

For Vaughan Williams, an agnostic yet one who composed hymns and was inspired by church music, this Phrygian mode was something of an obsession. He detected it in folk music and even used it in The Pilgrim’s Progress as the Christian pilgrim arrives in the Celestial City. Indeed, he had used this very same Tallis tune before, in 1906, when he composed incidental music for a stage version of the Bunyan allegory.

In his string fantasia, the Tallis theme has a grave, hymn-like quality, especially when set against shimmering high violins. Is it in G major or G minor? It seems to vacillate between the two. What gives the work its special quality is the scoring. It’s written for a double string orchestra – a main body of strings with a second ensemble of nine players distanced at the back. Sometimes this second orchestra softly echoes the first, or holds a chord, exaggerating the resonance of the building in which it is performed, seeming to give it a luminous halo. In a cathedral setting, the long reverberance can magnify this musical aura in a breathtaking way. In addition, the main ensemble is often pared down to an intimate string quartet, so you get three distinct textures, or choirs, within the string writing, echoing or responding to each other. As Vaughan Williams’ music grows to a climax, there’s a sense of searching for something that it never quite reaches. There is a resolution of sorts at the end, but we never return to that weightless first chord.

This is music of stained glass windows and cathedral cloisters, a piece that seems to work even better in a church environment than in the concert hall. I’m glad I first encountered it in Winchester Cathedral where, incidentally, my favourite recording of it was made (the BSO under Constantin Silvestri in 1967). You can see – and hear – how the spatial element conjures its magic in this performance recorded in Gloucester Cathedral by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under Sir Andrew Davis, who here also separates the solo quartet.

While the Tallis Fantasia, with its echoes of the English Renaissance, may sound “quintessentially English”, that first audience was thrown, as Herbert Howells later reflected. “The music… probably became in the moments of its first performance a great conundrum to a large part of that audience, so one can say by the end that it probably confused more than it converted.” Certainly, the cathedral organist, Herbert Brewer, was not a convert, describing it as “a queer, mad work by an odd fellow from Chelsea”.

Writing in the Manchester Guardian, Samuel Langford wrote that “The melody is modal and antique in flavour, while the harmonies are as exotic as those of Debussy.” The Musical Times reserved judgement. “It is a grave work,” its anonymous critic reported, “exhibiting power and much charm of the contemplative kind, but it appears overlong for the subject matter.” (Vaughan Williams later revised it, lopping about two minutes off the playing time.)

For me, John Alexander Fuller Maitland’s review in The Times judged it perfectly. “One is never quite sure whether one is listening to something very old or very new.” Exactly. Timeless.

Footnote: my thanks to Jennifer Baker for correcting my analysis of the opening chord sequence [MP, September 2025]