Carlo Rizzi has Italian opera running through his veins. Growing up in Milan, studying at the Scuola di musica, he first attended La Scala in 1972, a dress rehearsal for the big season opener Un ballo in maschera. His eyes light up as he reminisces about Plácido Domingo and Piero Cappuccilli “singing like gods” and Franco Zeffirelli’s impressive new production – “I can still picture it today. The scene change from the Count’s study to the ballroom in Act 3, it was incredible.”

“All my training, basically, was when Claudio Abbado was music director at La Scala. I was going there three or four times a week on standing tickets. It was the only time in my life when I was a little more athletic because I would run up all the stairs to get to the best places. Honestly, it was a stampede! Every night there was a great conductor, great singers, a great production. There was much more money, of course, in those days. It was incredibly formative: Abbado, Gianandrea Gavazzeni, Riccardo Muti. I remember Carlos Kleiber conducting Bohème and that famous Otello, Seiji Ozawa conducting Tosca… these are things you don’t forget easily.”

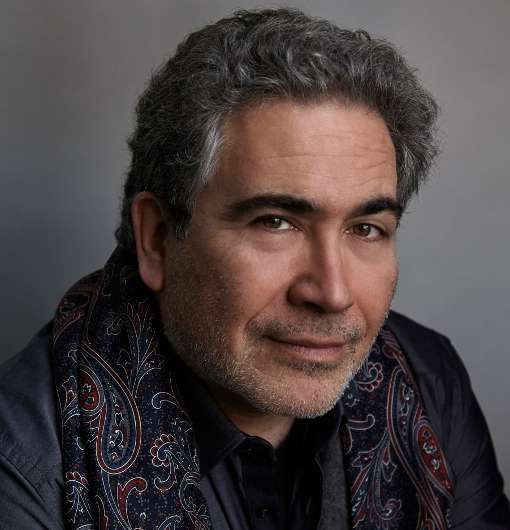

On graduating from the Milan Conservatory, Rizzi became a répétiteur at La Scala which launched him on a conducting career that has taken him across the world. When we met for coffee at Wigmore Hall, Rizzi had just returned from New York, where he conducted Norma, the big season opening production, and Turandot. He is famed for his Italian repertoire. Italian conductors, I remark, still dominate Italian opera, even if Italian singers aren’t the same force they used to be. For Rizzi, it’s an underrated art. “Every time I’ve done Norma I’ve always thought ‘this opera is too difficult’ because people think – and this really irritates me – that to conduct Italian opera is easy. You see a consonant at the end of the composer’s name and people think, ‘Ooh, difficult!’ This is utter nonsense. Actually, technically, Italian repertoire is much more complicated because it is based very often – particularly bel canto – on something that is not written. If it’s written in the score, you do it. If it’s not written, then it’s based on the words, on the accents, the flow of the phrase.

“In opera, of course, the conductor has a responsibility over everything but you have to measure your ideas against the people you are working with. If the conductor goes in with an idea that is inflexible, it would be like going to a car and wanting everything to work like a Ferrari. But it’s not a Ferrari and I ruin the car by driving it like a Ferrari. It’s the same with orchestras. Of course, I have to have ideas, otherwise I shouldn’t be on the podium, but you need to find the best from the orchestras and singers you are working with. There is no good reason for doing coloratura faster than the singer can manage it – either you decide to fire the singer or you have to adjust and work together to find the best way forward.

“This is what was great at The Met with Norma because we had the rehearsal time and I worked very closely with David McVicar.” Not all directors are so cooperative. “The problem is that with intelligent directors, you just talk through problems. With ones that are not, then it’s useless because they have an idea or a “concept” – a word that I hate – but what happens when the “concept” doesn’t fit the actual words which that poor idiot Verdi wrote?! In the way theatre is organised today, the music will always be second. When a theatre engages a conductor and a director, the conductor has done nothing before rehearsals begin other than study the score, but the theatre has already paid hundreds of thousands on sets and costumes. So what do you do? Do you throw it in the bin? It’s impossible.

“Many opera directors don’t start from the music, they start from the libretto. And we all know that a certain word said in a certain way with a piano accent accompanied by the strings is one thing, while the same word accompanied by trombones and a fortissimo accent is a different story. But there are not many directors who understand this. There are many that do, but many more that don’t and that, for me, is the main problem.

“Opera productions needs to work for the audience of today. It is a fact of life – and I don’t like it very much – that these days much more information goes through our eyes than through our ears. Just imagine if you had the news without any film or graphics! And it’s the same in the theatre. Everyone thinks that a new production means there has to be something new to see … but there is always something new to hear too. It’s important for the public to understand that they’re going to see an opera – the libretto cannot stand without the music.”

A look at Rizzi's schedule for the spring is alarming: touring Tosca and a new production of La forza del destino with Welsh National Opera, interspersed with trips to Berlin for Madama Butterfly and Rome for Cavalleria rusticana and Pagliacci, before a new production of The Tales of Hoffmann in Amsterdam, where last season Rizzi conducted DNO's new Rigoletto. He should be coining in the Air Miles!

How does he juggle such a busy diary? “It comes down to organisation. For example, I’ve never done Hoffmann before so, trust me, there’s no way I’m going to dip in and out of rehearsals. The same thing for Forza in Cardiff, which is the only major Italian opera I’ve never conducted before. There’s a difference between knowing the opera and being ready to go on the podium and conduct it. For the last three months I’ve been at The Met and all this period was dedicated to study of Forza. I’m not going to do things like landing at 2pm with a performance at 4pm, that’s stupid and not respectful of the public or your colleagues, so you need to know what your body can take and – considering my white hair! – what I can do today is less than what I could do twenty years ago!”

I suggest to Rizzi that Forza is finally enjoying a resurgence. Already this season there has been a new production at Dutch National Opera, with new productions in Dresden and Zurich to come following WNO’s which opens in February. “Forza is an opera where we need to have the singers,” he muses. “It’s a very demanding opera for the tenor, the soprano, the baritone and the smaller roles of Preziosilla, Padre Guardiano, Fra Melitone can be very complicated. Forza does have problems. Verdi reworked it so much. What we do with director David Pountney is to change around the order of some scenes a little and I hope Father Verdi will not send down a bolt of lightning! But then, he changed it many times himself. To be really honest, he changed it because he was not happy with the dramatic flow of the piece – the tenor is nearly killed in battle, yet two minutes later… tadaaaaa, he is saved! It’s an intriguing story though and the way Verdi uses the themes as leifmotifs is wonderful. We have a good cast and good rehearsals. I like working with David Pountney because, although he sometimes has quirky ideas, he understands what it means to put an opera on stage.”

Opera in Italy has often suffered in recent decades, making it harder to secure star names in what used to be prestigious houses. “I’m really sad when I talk to colleagues and their first question is ‘Do they pay you?’ because there is this financial problem. It is true that there are people who have not received money from six months ago, so the reputation of the house goes down.” Yet Rizzi maintains that standards in some houses are very high. “I did Tosca two years ago at La Scala and the way they played that opera was fantastic. Then I did Giordano’s La cena delle beffe there – the last performance there had been under Toscanini! – and it was interesting to see this orchestra rediscover part of its heritage. There is incredible talent in Italy and they played it brilliantly.”

In April, Rizzi conducts at the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome for the first time. I recall hearing a singer viciously booed there a few years ago and remark that British audiences are far more reserved (except when it comes to directors, but we get onto that later). “If you look on Youtube,” he confides, “there is a clip of Carlos Kleiber being booed conducting Otello at La Scala! I was there at that performance.” Was it the loggionisti, I wondered, or claques? “All the years I was at La Scala, the claque never booed. They were maybe not clapping, but they were there to applaud one particular performer.”

In Parma, the loggionisti see themselves as fierce defenders of Verdi and things can get quite heated. “At the Teatro Regio, when they opened the Verdi Festival many years ago with Rigoletto, it was a modern production. There were cross-dressers – but then again it’s an orgy – so when we got to the end of the first scene, the skies opened! Disaster! My colleague in the pit had to start the next scene between Rigoletto and Sparafucile which opens with just clarinets and bassoons… Forget it! The loggionisti were shouting, the people in the stalls then started to shout back at the loggionisti. It was crazy! Who gains from this?”

In London, things are far more restrained. “At Covent Garden many years ago – I think it was Trovatore – the tenor did something really horrific. Thinking about Italy, I said to myself ‘Now the audience will register an earthquake!’ yet all I heard was a collective sigh of disappointment, nothing more! It’s two different worlds.”

WNO's La forza del destino opens on 2 February and then goes on tour.