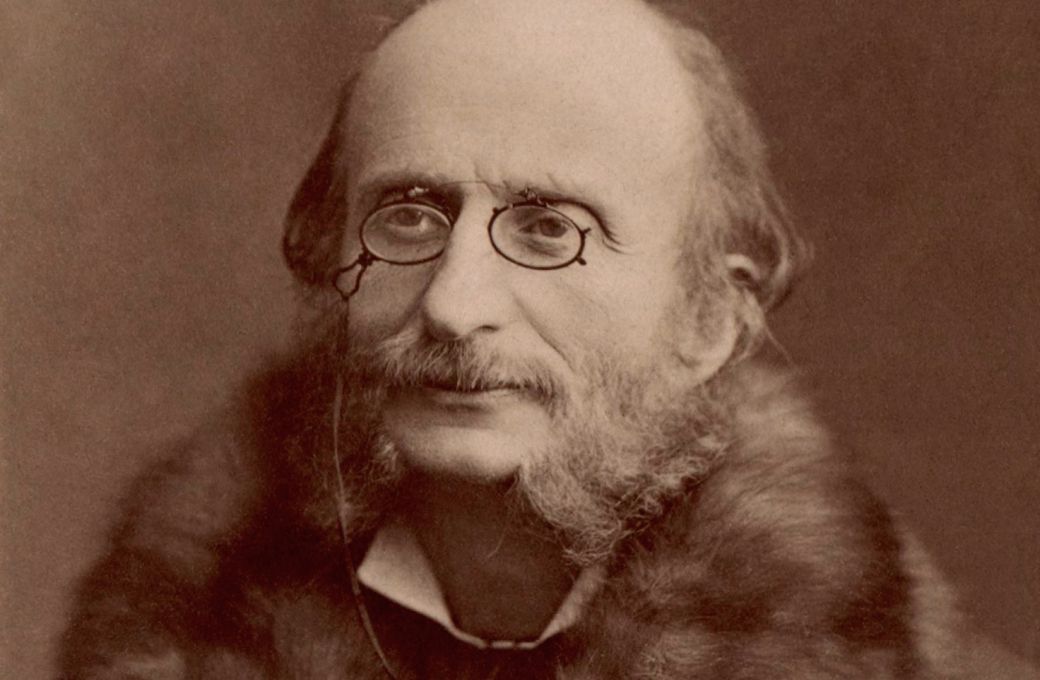

Jean-Christophe Keck is a conductor and musicologist. But above all, he is a lover of the music of Jacques Offenbach, which he has been editing for 20 years in the celebrated OEK (Offenbach Edition Keck), published by Boosey & Hawkes. On the occasion of the 200th anniversary of the composer's birth, this indefatigable, impassioned music lover talks about his past research, his present projects and his hopes for the years to come.

TL: How did your relationship with Offenbach start?

JCK: When I was 13 or 14, I watched a TV series called Les Folies Offenbach with Michel Serrault. I was thunderstruck, it was love at first sight: I immediately looked in my father's record collection to see if it contained any Offenbach and I found a version of La Belle Hélène. I became totally besotted by this music, in a way that was truly excessive.

I started buying records and scores, like a young collector. Gradually, Offenbach started to play a more important part in my life, up to the point where I made him my profession. From seven years old, I knew I wanted to be a musician, but I didn't yet know if I would be a conductor, a singer, a pianist… Things happened more or less by themselves: in around 1989, I relaunched the Association des Amis d’Offenbach with the intention of making known, and recording, Fantasio, which I had just discovered – although it didn't happen for another 30 years.

Was that the time where you started to work on the edition?

The first of my editions was done in 1991, for Opéra de Lyon: a staging of La Vie parisienne directed by Alain Françon… I fell into the project utterly by chance: I was visiting a publisher, Mario Bois, simply to find out what he had in the way of Offenbach scores. He explained to me that he was looking for someone to create an edition of La Vie parisienne in its original five act version, since there wasn't one available at the time. I asked “Why not me?”.

So I dived into the task, working day and night for a whole summer, but when I saw the way this exhausting work was treated, I said, “Never again, no more editing for me!” This was my first experience of editing but also my first experience of a production which included a Dramaturg, which is originally a German concept that you only saw in Regietheater at the time: the idea had not been seen in France.

So this Vie parisienne was one of the first productions where a Dramaturg arrived wanting to shuffle around the work's various numbers, make cuts in the middle of arias, reassemble things… Fortunately, the conductor, Jean-Yves Ossonce, was there to limit the damage; he had to put some things back into order but it was a constant battle! I thought that once I'd finished my work, what I had written would be performed, whereas the reality is quite different.

But some years later, in 1999, when my current publisher Boosey came to me to suggest that I engage in this monumental edition of Offenbach's work, I couldn't refuse the offer. And now, I've been working on it for twenty years! But I've changed my views: I've understood that you have to work for posterity. I put everything I can into my editions, the maximum amount of material possible – some of which, obviously, is previously unpublished. I'm giving the performers different paths, I inform them about what Offenbach wanted – but then I leave to them to sort it all out to the best of their ability and good conscience.

The question of respect for the original is a tricky one, even in your work: it's not unknown for you to compose in the style of Offenbach in order to complete one of his operas…

That only happened for Les Contes d’Hoffmann. Or when I've written orchestrations that were missing, for example for La Vie parisienne… But I defy anyone to distinguish what's written by Offenbach from what's written by me: my objective is always to fuse myself into the original work, not to inject my own ego.

The inconvenient truth is that I'm never truly “writing Offenbach”, because he always springs surprises on you! I'm reproducing certain ways of doing things that are found in other works, for example the way he writes a finale, but for sure, he would have done things differently. And it depends on which period we're talking about. In his youth, when he wrote a piece like the Ouverture à grand orchestre, his orchestration was very much inspired by Beethoven and Schubert. But later, everything that he composes in the operatic world has a Mozartian heritage, with a carpet of strings, with colours, with a fair number of woodwind interjections which are always light and transparent.

But because he was a genius and not a doer, there are no two orchestrations which are similar to each other. I'm currently working on a very rare overture which is going to be played in concert soon, Le Roman comique. At the end of this overture, I have no idea what he's trying to do with his orchestration, it's incredible! It's a kind of giant jumble with a trombone lumped in the middle – something he doesn't do anywhere else! If I'd had to orchestrate this passage, I'd have done it far more classically.

For a long time, Offenbach was poorly thought of, considered a mere entertainer. Today, there are seminars about him. 200 years after his birth, how do you assess how he is viewed?

Fortunately, things are changing! There have been several stages: in 1980, for the centenary of his death, there was a kind of renewal; people started to look at him in a new light. Around then, there appeared recordings of his cello works: we discovered an Offenbach who had been previously unsuspected. Later, people started working in this direction. It's been helped by the scores that brought to light in the l’Offenbach Edition Keck (Les Fées du Rhin, Fantasio). There's the celebrated recording by Anne Sofie von Otter and La Haine in Montpellier, which showed his sacred music: those contributed to us being able to see the composer in all his different facets.

I can still remember, when we did the London premiere of Fantasio, the extent to which the audience was discombobulated. I had elderly ladies say to me “but that isn't Offenbach!” They couldn't understand that he was able to write music in seria form. Now if you look at all his writing, even in his opéra-bouffes, there's always something sentimental and lyrical; that's what makes his alchemy, this mixture between madness and playing the clown. If you only take one of these two aspects at a time, you're completely missing the point.

What is there left to discover about Offenbach, and what sources have you not yet explored?

There are many things to make visible to the public at large. The main problem with Offenbach is that his legacy has been scattered across the whole planet, so I'm continually discovering new things. At the home of one of his descendants, I recently found a cupboard with an attic entirely packed with music! Everything from the first scores he wrote aged six or seven to the last pages of Les Contes d'Hoffmann, by way of Le Royaume de Neptune, the ballet scene from Orpheus in the Underworld which everyone thought had been completely lost. It was extraordinary! They allowed me to bring a scanner into the house; for three years, starting in 2013, I spent every weekend breaking my back on this machine. In all, I scanned 20,000 pages of scores. When you consider that an opera manuscript is usually around 300 or 400 pages, I'll leave it to your imagination as to quite the scale that this entailed.

It's all been magical. In 2016, I was getting ready for a conference at Komische Oper Berlin, just before the premiere of Barrie Kosky's Hoffmann, to explain where we were as regards the sources. Just before the conference, I received a text from the Offenbach family: they were doing some clearing out and getting rid of old papers. They sent me a photo just in case I was interested – it was the first notes on Les Contes d’Hoffmann. That's how we were able to recover the first two acts of the work [which were thought lost to fire at the Opéra-Comique in 1887: ed].

What are you currently working on?

We're just embarking on a new edition of Robinson Crusoé for Komische Oper. I'm happy to say that we have both the manuscript and the material of the premiere. We're also working on a new edition of Le Voyage dans la lune, which will be used in various houses in Germany.

There's also Offenbach the cellist. I've unearthed a fair quantity of pieces for cello and orchestra, cello and piano, two cellos… I'm hoping to work on these with my friends Jérôme Pernoo, Jérôme Ducros, Bruno Philippe and all these extraordinary young cellists.

And, of course, there's recording: in the course of 20 years, we've published 60 or so operatic works and, sadly, the discography hasn't been remotely keeping up. Theatre directors have done a fabulous job to get these works staged (I'm thinking about particularly about Fantasio) but the big labels are happier recording Carmen for the 150th time or Tosca for the 36th. Today, when a theatre's general manager or stage director is deciding what works to stage, they don't read the score: they're listening to recordings. So we have to give them some material, we must get this music on record! And I'll take the chance to tip my hat to my publishers: if there weren't publishing houses dedicating themselves to preserving our heritage, many works would be doomed to disappear.

Translated from French by David Karlin