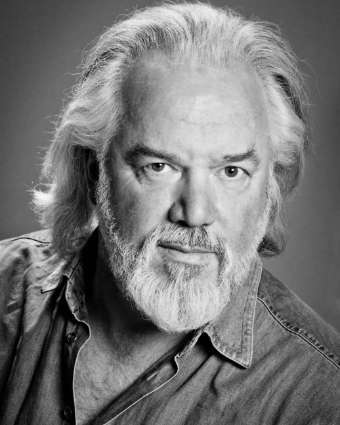

Opera houses are understandably cautious about the future, but they do have to plan several years ahead. He’s been asked to do the part of the lawyer, Swallow, in Peter Grimes at Covent Garden in 18 months’ time. No contract has yet been issued, but he says it’s a “definite engagement”. Doesn’t he find the lack of a contract concerning? “Contracts have been going out later everywhere over the last ten years. The planning’s been more short-term globally for some time now.”

“During the lockdown I’ve been working on something every day, mostly The Shackled King.” The latter is a new work written specially for him by John Casken. Back in 2016 Casken wrote a monodrama for him and the ensemble Counterpoise, Kokoschka’s Doll, in which he incarnated the artist Oskar Kokoschka as he relived tormented episodes of his younger life, including being gravely injured in the Austrian Army during the First World War and a tumultuous love affair with Alma Mahler: the piece is named after the life-size doll of Alma that Kokoschka commissioned to help him over the trauma of the relationship's demise. Based on the success of Kokoschka’s Doll, Counterpoise commissioned another work from Casken for Tomlinson, this time based on Shakespeare’s King Lear.

For a singer who has stormed the world’s stages playing troubled rulers such as Wotan, Boris Godunov and Ivan Susanin, the attractions of Shakespeare’s flawed monarch seem obvious. In fact, Tomlinson was drawn to the part many years ago and has studied the play in impressive depth, noting a number of parallels between Lear and Wotan. “Two projects, both involving Lear, came up, by coincidence, at the same time. The first is for a conventional staging of Shakespeare’s play but with opera singers taking all the roles: Tom Allen, Kim Begley, Susan Bullock, Peter Coleman-Wright, Christopher Gillett and many others. Keith Warner is directing and we’ll be doing it at The Grange and other venues.”

The other project is The Shackled King, which, like Dean’s Hamlet, will approach the work in a less traditional way, opening with the scene at the end of Act IV where Lear and Cordelia are reconciled, and refracting the earlier action of the drama through the mind of the now deranged king. A mezzo-soprano (played by Rozanna Madylus, who took the part of Alma Mahler in the programme featuring Kokoschka’s Doll) takes the role of Cordelia, doubling as Goneril, Regan and the Fool. “I wanted to use sections of Shakespeare’s text”, explains Tomlinson, “and weld them together for John Casken to compose. We had all talked about how this might be done. Then one day on a long train journey from Munich I had the inspiration. The focus on Lear and Cordelia was fundamental to the piece, as far as I was concerned. There’s a long separation between the two in the play and my idea was to start with them after they’ve been led away to prison [Act V, Scene III] and have them replaying the story. It was John’s idea to start a little earlier and show them half-remembering and half-asleep, so that we begin with a kind of awakening, then go back to the division of the kingdom in the first scene, then back to the awakening, which alternates with Lear’s loneliness and despair, the storm and the reunion with Cordelia’s death.”

Are there parallels here with the approach in Kokoschka’s Doll? “Yes, Kokoschka’s Doll starts in the artist’s studio and he begins to recall his past life: going off to war, his hospitalisation, the making of the doll and its destruction at a party. But we keep coming back to him in his studio and there are musical recollections too that bind it all together.”

The word-setting of The Shackled King and Kokoschka’s Doll has much in common too. I asked John Casken to describe how he went about it. “I worked closely with John Tomlinson”, he said, “and we explored how to use the gamut of vocal delivery, from pure speech, to heightened and dramatic delivery, to rhythmicised speech, to sprechgesang (distorted half-speaking/singing, so apposite for the portrayal of extreme psychological states), and to fully expressive singing, from the most tender and intimate to the most dramatic and operatic. Moving freely between these kinds of vocal delivery does not happen piecemeal, but sometimes within a single segment of text and it is this approach that I have continued in The Shackled King.”

But as Tomlinson points out, there are substantial differences between the musical representations of Kokoschka and Lear. “With Kokoschka”, he says, “there’s more drama: he’s more unpredictable and the declamation is livelier. With Lear there’s a profound humanity: we feel the dignity more, though as with Shakespeare it encompasses extremes from his raging in the storm to the most intimate scenes. It feels very natural for my voice”, he adds, “John Casken understands the way it works and enables me to capture the character’s introspection.”

How is he learning the role, I wondered, given that he’s “imprisoned” himself, down in Lewes, without the benefit of a pianist to help him learn the part? “Even in normal circumstances, I often use a recorder – a sopranino recorder, I mean, not a recording device – and I might also play harmonies on the piano myself, but then go away from the instrument to sing the line. Sometimes I’ve had to learn a part on a train and go straight onto a rehearsal studio. But with The Shackled King I have the benefit of a synthesised version of the score kindly provided by the pianist for the project, Yshani Perinpanayagam. It’s very helpful for getting an idea of the overall span of the part.”

It is hoped to do a couple of performances in connection with conferences on Shakespeare and Music in Manchester and Huddersfield in December.

Much will depend on the state of play with regard to Covid-19 closer to the time, though small-scale works of music drama like this might seem an obvious way forward until the big houses are able to throw open their doors once again to opera-starved audiences. Meanwhile, Sir John is finding the experience of working on another dramatic work specially tailored for him “very enjoyable”. He’s also relishing the “acres of free time, the absence of stress – though a certain amount of pressure in operatic activity is actually rather reassuring”. He and his wife Moya have been spending more time on the allotment, having “lovely walks in the countryside” and I also learned of a hidden talent for basket-weaving. The couple make baskets from willow trees they planted fifteen years ago in a variety of species and colours from yellow, green and brown to purple and black. He held an exquisitely made black basket up to the camera for inspection. Recently they’ve been making more than they need for themselves and have been giving them away. A second career beckons, perhaps, if things don’t get better soon.

Kokoschka’s Doll was released on the Champs Hill label in January.