There’s a straightforward mission underpinning the video streaming platform Symphony.live: to gather together the world’s great orchestras, as a community, for the benefit of all. To broadcast their best performances to classical music fans, wherever they are, whether they’re an orchestra’s regular attendee or someone who lives miles from a concert hall.

But is that a vision of the future, or a pipe dream? Maarten Walraven and Jeroen van Egmond have been co-CEOs of Symphony.live since June this year, so to get a view on the present and future of streaming, I spoke to them by video call to the company’s offices in Amsterdam.

We’ve certainly come a long way since 2008, when the market for video streaming of classical concerts came to life with the arrival of Medici and the Berlin Philharmonic’s Digital Concert Hall. A decade and a half later, the diversity of choice available to concert lovers has exploded, with countless orchestras filming their concerts, and streaming choices ranging from orchestras’ own offerings to traditional national broadcasters – as well as aggregators like Symphony.live. So how do Walraven and van Egmond assess the current market?

Walraven is sure that “even though it’s fifteen years later, the promise is still there. When you look at the total addressable market, it’s still huge. And we all agree that none of the existing video streaming platforms have cracked the code to getting the big numbers of people on board. So there is still an opportunity to get to those people”.

Giving users what they’re searching for

Because it’s all digital, streaming generates a treasure trove of data to learn from. “The seasonality is really big. For streaming as a whole, you see that the winter months are the most interesting. When it starts raining and getting cold, people stay in and they start streaming content. Searching for classical music streaming is at its highest level from October until February/March. In spring and summer, it’s still there but it’s much lower.” Within the week, people mainly stream concerts on a Sunday, as opposed to live concertgoing, which is most probably on Friday or Saturday.

What are streaming users searching for, I ask. “From the data we are getting, it’s often quite broad, either for ‘classical music’ or ‘stream classical music’ – especially the second. They will search for specific orchestras, but there’s a lot of broad search for the category.” On their own platform, van Egmond says, there are also composer searches. “They look for the most famous composers first – frequently Beethoven and Mozart. There are some users who search for very specific things, but most people on the platform just play whatever is served to them. The video that gets the most clicks is the one we present on the hero banner at the top.”

In audio streaming, a music lover can essentially get all the music they want from a single subscription to Spotify (or one of its more classical-oriented alternatives, as explained in our article). But when it comes to video, the content is far more scattered and choice is dizzying. You can spend your money on a subscription to a single orchestra’s platform (the biggest is the Berlin Phil, but there are plenty of others), you can take your chances on an ad-free YouTube plan, or you can go to Symphony.live or their various competitors. The general video platforms are also clamouring for your subscription money: Netflix, Amazon Prime, Disney+ and countless others. How many subscriptions is it reasonable to expect a person to have?

Video is a totally different experience from audio, Walraven explains, because the industry is structured so differently: “There’s a lot of exclusivity – people doing their own content. And people with kids are different, because you then need other things. In affluent Western markets, some people might end up with five to eight subscriptions. MIDiA research says that when people look at their spend, they will first try to avoid cancelling things and rather choose to do less of something. So if you’re somebody who goes to concerts, you might go to one fewer concert – but then take a video streaming subscription.”

But is the market growing? Walraven and van Egmond “want to say yes”. All their pre-launch research indicated a strong appetite for streaming and a strong willingness to pay. But one barrier Walraven cites is the critical moment when the platform asks the user to provide their payment details.

It’s not the only area where what consumers say and what they do are two different things. For example, the question of whether the platform should augment the music with information and story-telling, or just show the concert. “Whenever we do surveys,” van Egmond says, “we get the feedback that people want to know more about the music, about the underlying ideas behind a certain symphony or concerto, know more about the orchestra or the players. Then we look at our viewing data, and we see that people just watch the music. But we still firmly believe that the only way to reach that bigger market is to provide them with the information that will lead them into more enthusiasm for the music.”

Classical music’s digital transformation

Regardless of the growth prospects for paid streaming subscriptions, Walraven is very clear that orchestras have a huge appetite for what he calls “a general digital transformation within classical music”. Simply put, if orchestras want to keep in touch with their audiences, they’re going to be forced to do it online – and providing videos of their concerts is going to be a key component. All the orchestras he speaks to have said that this forms part of their strategic plans. Some, he says, have a pure motive of earning money from their videos: “we’re talking to a lot of orchestras who say that they are struggling, that people are not going to the venue. They have to find new revenue models.” The biggest challenge, it turns out, is performance rights: many orchestras have contracts with musicians that were drawn up long before streaming video existed. Untangling the legals and negotiating with musicians and their unions can be a complex and lengthy business.

Exactly what kind of video is also an open question. “A lot of the standard videos are shot with multiple cameras, with the orchestra sitting in their hall. And the halls often look very similar. And the people on the stage often look very similar. So how do you differentiate yourself? Well, either you have the big budget things that come from Germany, with the public broadcasters behind them, where they do all these crazy things with cranes and lots of moving cameras.

“Then you have orchestras like the Danish National Symphony Orchestra who almost move beyond the audience and towards the video – they think much more about lighting, much more about staging, and that there’s something else to look at besides the players. But let’s think about what viewers want. We know that not many of them watch a full hour and a half concert. So why not create formats that are 20–30 minutes long? And an informative format, where people will learn something along the way? There are many different ways to look at it.”

Van Egmond points at an example “from a whole different category” – André Rieu, whose production team use a lot of audience shots, bringing the viewer into the atmosphere of the gig in a way that is rarely done in classical music videos. “You see smiling people, you see dancing people. Again, it’s a different category, it’s different from what we are doing, but from a filming perspective, I think what they do is great.” (Could such heart-on-sleeve enthusiasm can be conjured up from symphonic audiences? One wonders...)

Joining the party

Symphony.live’s pitch to the viewer is twofold: firstly, the richness of content on their platform from many different orchestras, and secondly, that by subscribing to the platform, the viewer is supporting their orchestra. Van Egmond explains: “We have a revenue-share model and a commission-based model. So by choosing Symphony.live, they will help the orchestra they are a fan of and are also able to see all these other orchestras around the world.”

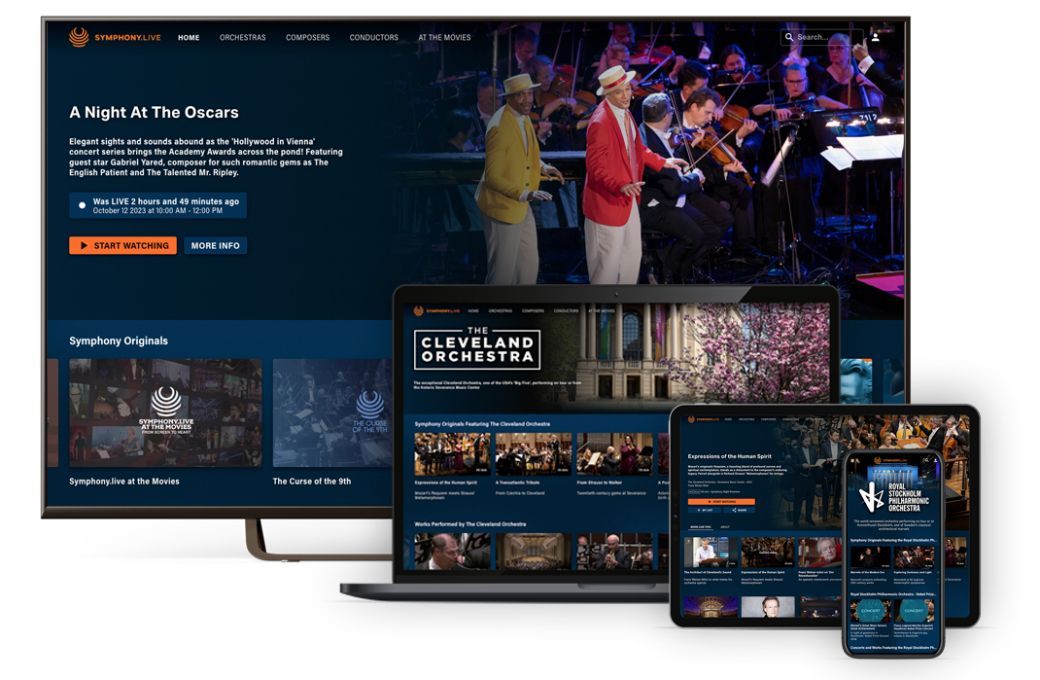

With most orchestras already sold on the idea of doing video, Symphony.live’s task is to achieve what Walraven calls “the flywheel effect” of getting as many of the world’s great orchestras as they can onto their platform. There are eleven right now and Walraven and van Egmond will be fully focused on increasing that number. They cite three reasons to be confident of this: firstly, that unlike other platforms, Symphony.live is genuinely dedicated to orchestral music which provides each orchestra with a proper presence on their website. Secondly, that they are providing a lot of technology which is difficult or expensive to replicate, whether it’s in viewer analytics, or support for a plethora of viewing devices. And thirdly, that their revenue-sharing business model will appeal to orchestras themselves. The dream is clear, the creation of “a central place dedicated to video streaming of symphonic and classical music – and a family of orchestras from around the world who profit from working together on this platform.”

Symphony.live subscriptions are €6.99 a month, or €49.99 a year. The platform is available online, via iOS and Android apps, and via streaming digital TV.

This article was sponsored by Symphony Media.