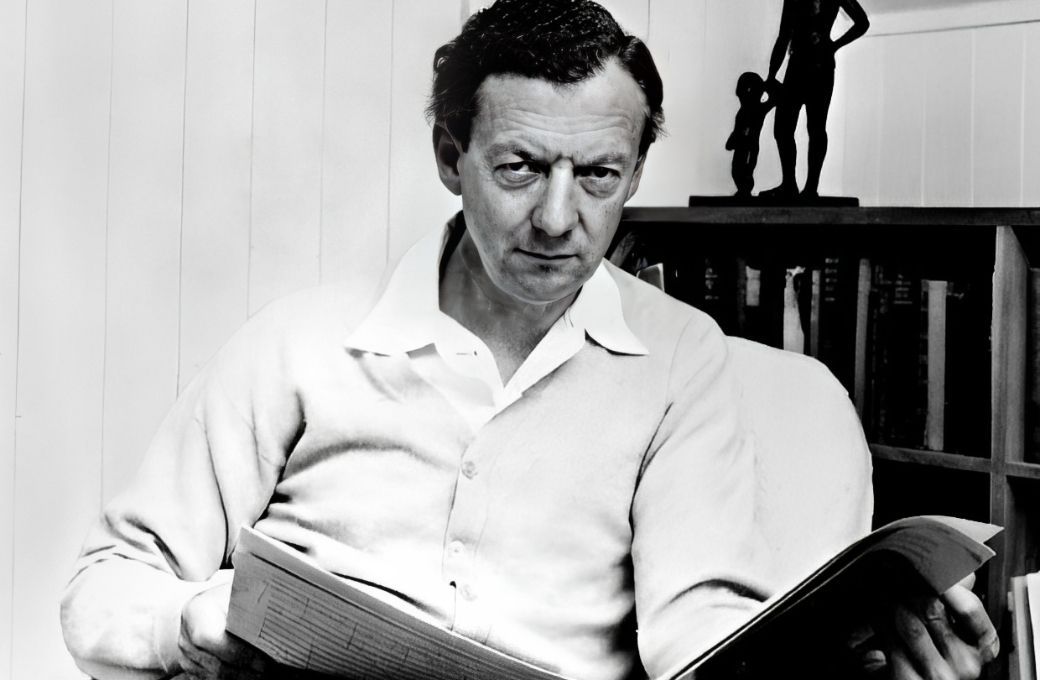

Who was the finest British composer of the 20th century? Elgar and Vaughan Williams both stake their claim, particularly in the symphonic realm, but for many Benjamin Britten would take the laurels. Britten took a very different compositional route than his predecessors. Symphonic music was not for him; he wrote only a handful of purely orchestral works. Britten was fascinated – almost to the point of obsession – by the human voice and the vast majority of his works are songs, choral music and opera.

Many of those songs and operas were written for the tenor Peter Pears, Britten’s life partner. The two made their home together in Aldeburgh, in Britten’s native Suffolk, where they set up the English Opera Group, which led to the foundation of the Aldeburgh Festival, still going strong to this day. Britten composed many works for the festival, including the operas The Little Sweep, Noye’s Fludde, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Death in Venice and the three church parables. Britten and Pears also invited high profile artists to perform at the festival, not least Mstislav Rostropovich, Galina Vishnevskaya and Sviatoslav Richter. Britten was also a fine performer, both pianist and conductor. In June 1976, he was created a life peer, the first composer to be elevated to the House of Lords.

As a homosexual (illegal in the UK for most of his life) and a pacifist, Britten perhaps saw himself as an outsider. There is much pain and darkness in his music – depicted in the tortured figures in his operas and in his songs and chamber music too. “It is cruel, you know, that music should be so beautiful,” wrote Britten to a friend in 1937. “It has the beauty of loneliness of pain: of strength and freedom. The beauty of disappointment and never-satisfied love. The cruel beauty of nature and everlasting beauty of monotony.”

One of the 20th century’s other genius composer-conductors, Leonard Bernstein, heard that pain too. In the introduction to Tony Palmer’s documentary A Time there Was, Bernstein says:

“Ben Britten was a man at odds with the world. It’s strange, because on the surface Britten’s music would seem to be decorative, positive, charming… and it is so much more than that. When you hear Britten’s music – if you really hear it, not just listen to it superficially – you become aware of something very dark. There are gears that are grinding and not quite meshing and they make a great pain. It was a difficult and lonely time. Yes, he was a man at odds with the world in many ways… and he didn’t show it.”

1Peter Grimes

The premiere of Peter Grimes at Sadler’s Wells in 1945 was a huge moment, launching a British operatic renaissance. The story of an outcast fisherman is based on a section of George Crabbe’s long narrative poem The Borough, a small fictional town, but one which strongly resembles Aldeburgh, Britten’s home. After the death of his apprentice – due to “accidental circumstances” – Grimes takes on another boy, with equally fatal consequences when the locals bitterly turn on him. In “Now the Great Bear and Pleiades”, the rough fisherman displays an other-worldly, poetic side.

Britten’s outstanding score also contains four interludes evocatively depicting the sea in its different moods, which have become popular concert works.

2Serenade for tenor, horn and strings

Britten’s most popular song cycle was written for Peter Pears and the great horn player, Dennis Brain. Composed at the same time as he was working on Peter Grimes, it sets English poetry on a nocturnal theme – from lengthening pastoral shadows and faint bugle calls to more sinister themes around death and decay. The cycle is framed by a horn solo played as prologue and, off-stage, distant epilogue.

3String Quartet no. 2 in C major

The C major string quartet was composed in 1945, after the great success of Peter Grimes, which had been lauded as the most significant English opera since Dido and Aeneas. In this string quartet, Britten pays homage to the genius of Henry Purcell. The premiere took place at Wigmore Hall in 1945 in a concert to mark the 250th anniversary of Purcell’s death. The final movement was given the Purcellian title of “Chacony” and is a set of 21 variations on a noble theme. Britten was fond of theme-and-variation technique, which he also employs in the long opening movement, while the short Scherzo has a vicious, almost Shostakovich-like bite.

4War Requiem

Coventry Cathedral was destroyed during a fierce bombing raid during the Blitz. Britten’s War Requiem was composed for the consecration of the new cathedral in 1962. It interleaves the traditional Latin Requiem Mass, featuring a soprano soloist, with poems by Wilfred Owen, who was killed in the trenches in World War 1, just a week before the Armistice. Owen’s words are hauntingly set as two soldiers on opposing sides – Britten memorably cast an English tenor (Pears) and a German baritone (Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau).

On the title page of the score, Britten quoted Owen:

My subject is War, and the pity of War.

The Poetry is in the pity...

All a poet can do today is warn.

5The Turn of the Screw

Britten’s chamber opera, with a brilliant libretto by Myfanwy Piper, is based on Henry James’ disturbing novella. It is a gothic ghost story about a young Governess sent to the country to look after two troubled children, whom she is convinced are tormented by the ghosts of a previous manservant (Peter Quint) and governess (Miss Jessel). It is never clear (in most productions) whether the children can really see these ghosts or whether they have wormed their way into the Governess’ imagination.

Britten again deploys a theme-and-variations approach, the prologue and 16 episodes of the opera connected with variations of the 12-note “Screw” theme, which interleaves two whole tone scales. Here is the Prologue and a later scene from Louise Muller’s superb Garsington production:

6Violin Concerto

Britten’s Violin Concerto deserves to be much better known. It was composed under the shadow of the impending Second World War, when Britten and Pears, as committed pacifists, had moved to the US. Britten had been overwhelmed by the experience of hearing the world premiere of Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto in 1936, and his own work has a similar “concerto-as-requiem” feel. The timpani strokes at the start, which become an obsessive ostinato, evoke another violin concerto – Beethoven’s – while in the finale, Britten uses passacaglia form, a set of variations in the tradition of Baroque chaconnes, which he deployed in other works, not least Grimes and his Second String Quartet.

7A Midsummer Night’s Dream

Written for the 1960 Aldeburgh Festival, Britten and Pears fashioned the libretto themselves, only adding a single line of their own to Shakespeare’s original text (“compelling thee to marry with Demetrius”). Where the Bard opens his play in the Athenian court, Britten plunges us straight into the woods, a nocturnal world ruled by warring fairies Oberon and Tytania (Britten’s spelling), where the meddling Puck runs amok among the human visitors. Britten cast Oberon as a countertenor, an ethereal sound to blend with the coloratura soprano required of Tytania.

8Variations on a Theme of Frank Bridge

Britten was a child prodigy and began his studies with Frank Bridge when he was a teenager. “Even though I was barely in my teens,” Britten wrote, “this was immensely serious and professional study; and the lessons were mammoth. I remember one that started at half past ten, and at teatime Mrs Bridge came in and said, ‘Really, Frank, you must give the boy a break’”.

Boyd Neel and the London String Orchestra were invited to play at the 1937 Salzburg Festival in August. One of the conditions, however, was that they premiere a work by a British composer, so Neel commissioned Britten, who obliged with a brilliant set of variations borrowing a theme from Bridge’s Three Idylls. Each variation is in a different genre or popular style, from Italian aria to Viennese waltz.

9Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra

There cannot be many works commissioned by the Ministry for Education which have gone on to achieve worldwide acclaim! Britten was asked to write a work that would introduce children to the different instruments of the orchestra. His Young Person’s Guide fits the bill brilliantly. The subtitle is the giveaway here: Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell. Yes, it’s another theme-and-variations game, the Rondeau from Purcell’s Abdelazer given a dazzling treatment as each section of the orchestra gets to strut their stuff before Britten’s then puts all the parts back together again.

10Les Illuminations

This cycle, setting the symbolist prose-poetry of Arthur Rimbaud, has long been the preserve of tenors ever since Peter Pears recorded it in 1953. But despite Pears being the dedicatee of Being Beauteous, the cycle was actually written for French-Swiss soprano Sophie Wyss, who gave the premiere in 1940. The cycle opens with Fanfare, with violas (in B flat) and first violins (in E) in competition, struggling for supremacy, leading to a Brittenish pun as the singer declares “I alone hold the key to this savage parade!” There’s a lot of text for the singer to get their tongue around in these tricky songs, which require plenty of character to perform successfully.

Hymn to St Cecilia

As a bonus, as Britten was born on St Cecilia’s Day (22nd November), here is his Hymn to St Cecilia, composed in 1942. St Cecilia is the patron saint of music and there was a long English tradition of writing odes to her – not least by Britten’s hero and muse, Henry Purcell.