Following a triumphant opening concert and a fabulous opera, the Göttingen International Handel Festival pulled off a hat trick of excellence with the oratorio Belshazzar. Concerto Köln was conducted by Czech Baroque specialist Václav Luks, featuring the NDR Vokalensemble and a sparkling array of soloists.

The text for Belshazzar was written by Charles Jennens, who sent it to Handel in 1744. It was based on several bits of the Old Testament with helpings of the 5th-century Greek historians Herodotus and Xenophon. Perceiving it to be overlong, Handel took a fairly ruthless pair of scissors to Jennens’ original, and a more streamlined version was offered to the public in 1745 at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket, London. It was revived at Covent Garden in 1751 and 1758, and some airs were resurrected from Jennens’ original on those occasions. The version presented at Göttingen was that of 1745, so those latter airs were not included.

Luks led the orchestra with wonderful energy and commitment, varying the tempi and tone according to the context to create an exciting sound world. The overture was sumptuous yet transparent, sometimes busy but always coherent, with delicately lucid passages. NDR Vokalensembe are a familiar choir at Göttingen: very powerful when appropriate, disciplined and with good English diction. Representing at different times Jews, Babylonians, Persians and sometimes just a general chorus, they excelled at every turn. "Recall, O king, thy rash command!", sung by the chorus of Jews, featured a great slow crescendo, from a restrained warning to a powerful rebuke. "Ye tutelar’ gods of our empire", the Babylonian chorus, was mostly full bore, but it also contained subtleties of texture and dynamics. The chorus at the end of Act 2, "O glorious prince", contains only two lines of text, but it thundered majestically along with trumpets and timpani, garnering warm applause. The final "Amen" chorus was equally rousing and led to a sustained ovation.

Nitocris was sung by Trinidad soprano Jeanine De Bique, who cut a stunningly regal figure in a black frock with glittering neck piece. She has a slight huskiness in her otherwise pure voice and excellent diction. "The leafy honours of the field" featured flowing but well-articulated, gentle coloratura, exquisite in every way. "Regard, O son, my flowing tears" was deeply heartfelt. "O dearer than my life forebear", her duet with her willful son Belshazzar, saw Nitocris sad and concerned; Belshazzar was exultantly defiant in his subsequent aria, "Not to destruction but to delight". In another duet with Cyrus – when she yields to his supremacy, and he offers himself as her new son – De Bique delicate and moving.

The role of Belshazzar was taken by young Spanish tenor Juan Sancho, who is quite a ball of energy. "Let festal joy triumphant reign" produced palpable excitement and real enthusiasm. Canadian-Greek mezzo Mary-Ellen Nesi is well known to audiences for her command of Baroque technique – a powerful voice with an equally powerful presence. As the Persian commander Cyrus, she looked the part in a black tunic with coloured band around her waist over black pants. All her airs featured excellent coloratura passages and stunning da capo cadenzas. "Destructive war, thy limits know" was a particularly exciting rendition with trumpets and timpani, fluid coloratura and one of those great cadenzas.

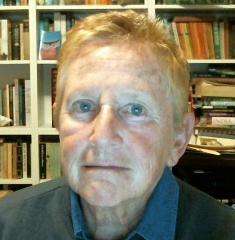

Daniel was sung by countertenor Raffaele Pe, who displayed strong high notes despite a rather low tessitura. "Thus said the lord to Cyrus" was very committed and compelling. "No: to thyself thy trifles be" produced some quite golden notes. There were some slight glitches in his recitatives and accompagnati, but overall he produced a compelling performance, the moral centre of the work. Likewise, Swiss bass Stephan MacLeod as Gobrias embodied Cyrus’s stalwart general with very powerful singing. "Behold the monstrous human beast" was sung with relish. He equally carried off an authoritative "Amaz’d to find the foe so near", tossing off thrilling high notes and a stunning cadenza in the da capo.

Overall, this performance reinforced Handel scholar Ruth Smith’s view that staging the oratorios prevents the audience from letting their own imaginations fill in the staging. One could not imagine a more exciting presentation, due "only" to musical and dramatic excellence of all the performers. A German colleague told me it was the best oratorio she had ever heard; it was clear from the reception that many in the audience thought the same.