The orchestral prelude is playing. Herman is wandering St Petersburg alone. A set of giant tarnished mirrors parts to reveal a hectic gambling scene, then a young woman, Lisa. They become Herman’s twin obsessions; the former will destroy the latter, and then Herman himself. No one has sung a note, but a tragedy has been foretold. It is typical of Garsington’s intelligent and insightful new production of Tchaikovsky’s The Queen of Spades.

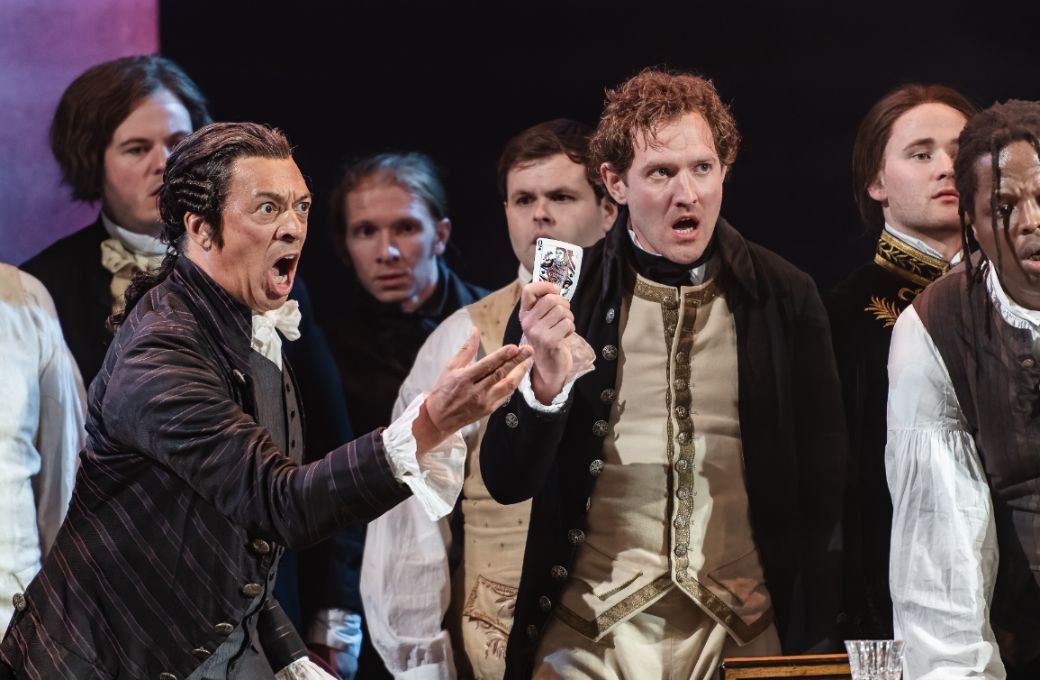

Designer Tom Piper’s mirrors were first seen in Garsington’s 2016 Eugene Onegin. Here they are often moved to reshape the performing space, even the backs are used to show impoverished interiors, the reverse (literally) of the city’s public glitter. 18th-century costumes underline social status, the lower order females in Russian folk dress, the quality with robes à la française, bonnets and parasols (becoming parapluies when a storm breaks). Gentlemen wear elegant knee breeches and tricorne. So scenes are handsome to look at, but at times haunted by drunken gamblers and disturbing onlookers, whether living ones like Herman, or revenants like the aged Countess he frightens to death, or her youthful incarnation.

Movement Director Lucy Burge animates these scenes such that the narrative flow is clear in this tale of natural developments accelerated by supernatural ones. Director Jack Furness elicits convincing portrayals of each character, major and minor, in an opera with many named roles. Above all the interactions between them are persuasive, especially between Hermann and Lisa, whose love and its unhappy outcome produce some compelling drama, as Herman’s gambling addiction, or rather its corollary fixation on a secret card sequence, supplant the love so passionately declared not so long before.

Not everything works well. Lisa’s drowning is not ideally revealed by hands lifting her aloft, and floating her offstage (woe betide anyone who had not read the synopsis). Perhaps a leap into the waters below à la Tosca was thought too banal. And Hermann’s gunshot at Catherine the Great made a gratuitous end to the first part, when evidence of his disintegration had till then proceeded more gradually.

Herman was sung by Aaron Cawley, whose experience (mainly on the continent) as Don José and Otello stood him in good stead for this vocally strenuous and histrionically taxing role. He has a fine tenor sound, with an impressive high register, and a baritonal warmth in the middle voice. In this space he was too loud at times, especially on high notes. But that added to a sense of a character close to losing control – one was not surprised when the Countess complained he had disturbed her rest. His stage manner among colleagues was ideal for suggesting a man who was with them, but not of them. A former Alvarez Emerging Artist, this was an impressive Garsington main role debut.

More completely satisfying perhaps was the Lisa of Laura Wilde, her appealing timbre allied to good phrasing and an abundance of passion that never threatened her control of beautiful sound. She acted persuasively, even in extremis (a frequent state for Lisa, who sees in Herman “the beauty of a fallen angel”). Her friend Polina was the excellent mezzo-soprano Stephanie Wake-Edwards, singing superbly at Lisa’s Act 1 engagement party, and leading that indecorous Russian peasant dance. Diana Montague’s Countess was imperiously dismissive of much going on about her, and sang very well in her long Act 2 scene recalling her youth as the “Venus of Moscow” admired at Versailles, seated beneath her (living) portrait.

Count Tomsky was Robert Hayward, the bass-baritone who has sung everywhere – except Garsington, until now. He sang very well in his opening scene narration, giving the backstory of the Countess and her valuable secret, if less so in his final scene contribution, which of course his character was reluctant to sing. But he threw off his coat and indulged the gambling set before the opera’s tragic denouement. The evening’s vocal honours went to Prince Yeletsky, a character not found in Pushkin, invented for the opera as the rival true lover of Lisa, and given the score’s best aria. Roderick Williams bought his familiar vocal qualities to this melodic gem, and provoked loud approval from the audience, led by a loud ‘bravo’ from a gentleman in Row K.

Conductor Douglas Boyd directed all this, plus the Garsington Opera Chorus, Garsington Opera Youth Company and the Philharmonia Orchestra, with the close control needed. If the Act 1 quintet was not quite together initially, perhaps because the five characters were spread right across the wide stage, it was soon in step. Above all, Boyd found the cumulative tension in this powerful operatic psychodrama, right up to its tragic conclusion.