This article was updated in July 2025.

The influence of Jean Sibelius as a symphonist was far-reaching. Indeed, his symphonies comprise the major portion of his body of work. He is largely identified with the symphonic form, and his natural tendency to think symphonically has been compared to that of Beethoven. Both Ralph Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax dedicated symphonies to Sibelius, and the composer’s symphonic style surfaces in the works of other British symphonists such as William Walton.

In his youth, Jan Sibelius was every inch a violinist, and the only concerto in his lifetime oeuvre was his Violin Concerto. Young Janne’s deepest desire as a teenager was to become a violin virtuoso. That was also around the time he adopted the French form of his name, Jean. Though his Swedish-speaking father Gustaf wished for his son to study law, Jean abandoned his studies at the Imperial Alexander University to matriculate at the Helsinki Music Institute (now the Sibelius Academy), and went on to study violin with Karl Goldmark in Vienna. However, Jean soon realised he had waited too long to become serious about the violin.

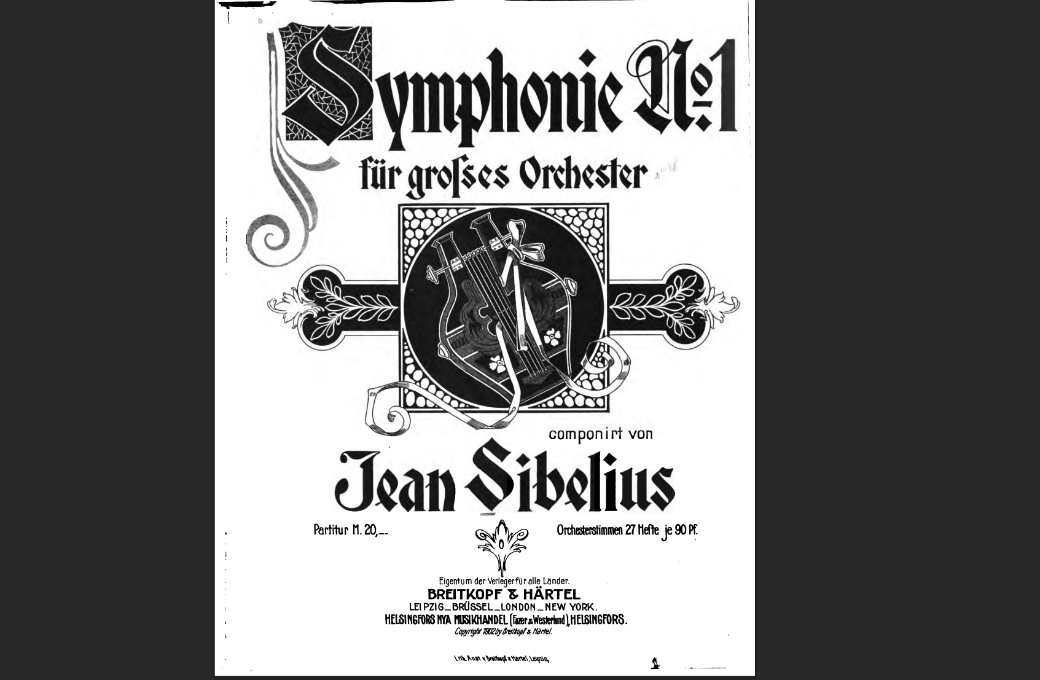

Nonetheless, a passion for this beloved instrument stayed with Sibelius throughout his composing life, as demonstrated in his Violin Concerto. The violin writing in other early works, specifically his first two symphonies (1899-1900 and 1902, respectively), also shows a deep understanding of the instrument’s challenges (as well as the influence of Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto in D major). These first symphonic works embody the young composer’s passion and fiery energy, as well as his brooding, youthful rebelliousness; and though they present considerable demands to the orchestra’s violin sections, the compositions are in all aspects a pleasure to play.

An orchestral violinist always appreciates opportunities to soar to the heights with magnanimous melodies and surge upwards with streams of rapid-scale passagework. These orchestral writing techniques in the first two Sibelius symphonies evoke similar passages that occur in Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty and Nutcracker ballets. The Symphony no. 1 in E minor provides these techniques in great profusion, starting with the initial Allegro energico section (in the composer’s initial programmatic concept, “a cold, cold wind blowing from the sea”) which appears after the brooding solo clarinet introduction (at 1'26" in the clip below):

From the conductor’s perspective, the composer’s First Symphony is both impressive and challenging. “I don’t know anybody who wrote a first symphony like Sibelius,” says [former] San Diego Symphony Music Director Jahja Ling. “It’s not only revolutionary and a stunning breakthrough, but I think after Berlioz, no other composer wrote a first symphony with that kind of impact. To score that symphony with the solo clarinet telling the story and the timpani murmuring – such a mixture of melancholy, cold and distant but at the same time heartrending. He already had so much to say.”

In the first movement development, a uniquely startling moment occurs when virtually the entire orchestra fades into the background to allow both the concertmaster and the principal second violinist a few measures of brief but ecstatic solo playing (5'38" above) in which the writing lies firmly and beautifully in a comfortable range for each. The chromatic episode of the development requires the violins to play with a youthful appassionato reflective of the composer’s own passion. It’s not so easy, but this leads up to the coda, a sighing lament building up to the ending.

The second movement begins with a poignant violin melody reminiscent of the opening Andante of the Violin Concerto. Later, pulsating woodwinds provide a background for a haunting cello solo, echoing the initial violin melody.

In the fourth movement, both violin sections burst into unbridled passion with their glorious, soaring B major melody, only to return to the dark, introspective nature that characterises most of the work. But the composer’s final pizzicato chords, if somewhat bewildering, seem to pave the way to the surprising bursts of Italianate sunshine and rainbows of colour characteristic of the opening of his Symphony no. 2 in D major, presaging sections of the Violin Concerto that followed just three years later, in 1905.

The First Symphony is less often performed than the Second. Ling, who also has performed Symphony no. 2 more than the First, thinks this is not because one is more difficult than the other, but because of the abrupt ending to the fourth movement. “You want him to end with that glorious sound, like that magnificent coda of the Beethoven Fifth,” Ling explains. The First is “more a reflection of the Beethoven pastoral, with a two-note ending almost like an Amen”.

Both Sibelius’ Symphony no. 2 and the concerto, in the classically violinistic D major and D minor, respectively, begin with a first movement Allegretto moderato. The Violin Concerto starts out in 2/2 meter, but the second theme of the concerto is stated in 6/4. The first movement of the symphony starts out in 6/4 meter, but with a repetition of notes and rhythmic motif, as if you don’t know what he’s trying to say or where he’s going until the ending of the movement. Those thematic first few bars with the same five notes continue throughout the first movement.

The Second differs from the First Symphony not only in its contrasting character overall, but specifically in its writing for the violins. In the first movement, they stand alone in their declamatory unison melody, descending from its beginning in an upper register to a passionate concerto-like G-string finish. Similar contrasting writing appears in bursts during the development, interwoven with brass and winds. The violins embody the warmth of the work’s passion, in stark contrast to the cold, almost menacing passion of the previous symphony: with complete abandon, and most often lying in the juiciest range of the instrument.

The scherzi of these two symphonies are wildly contrasting; the former Beethovenian in character, the latter more like a Mendelssohn scherzo. The final movement of the Second is glorious, with its ostinato and its chorale-like ending. In this movement, the composer’s deep love for the violin is, as always, heightened and in the foreground, as it is in the First Symphony.

In these two monumental symphonies, written in his youth when he still felt a profound closeness with the instrument that originated as and remained his passion, Sibelius blessed orchestral violinists with expansive melodies, challenging passagework, and the opportunity to shine. Like his Violin Concerto, the first two symphonies are as demanding and challenging for violinists as they are for conductors, but always a joy to play.