A seminal figure in American modern dance, Paul Taylor’s choreographic range is vast, but what permeates his canon is a relationship between physical athleticism, wit and the sense we are meeting individual people on stage. Making their Linbury Theatre debut and a welcome return to the UK after two decades, Paul Taylor Dance Company looked bright in a performance of two contrasting Taylor works and a company premiere by Resident Choreographer Robert Battle.

Brandenburgs is a strong manifesto of Taylor’s ideas. In handsome costumes of sage green and gold by Santo Loquasto, the dancers glide through Taylor’s answer to selections from JS Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos. A radiant, Hellenistic tone suffuses the whole dance, with Taylor adopting the baroque idea of counterpoint: a trio of women and a central male figure operate outside and within a quintet of athletic men. Taylor’s work emphasises the broad, sweeping breadth of the dancers back in motion, against the complex use of the feet. Though walking, running, and loping triplets abound, much of Brandenburgs’ ornamentation is taken from the high-baroque of ballet’s vocabulary.

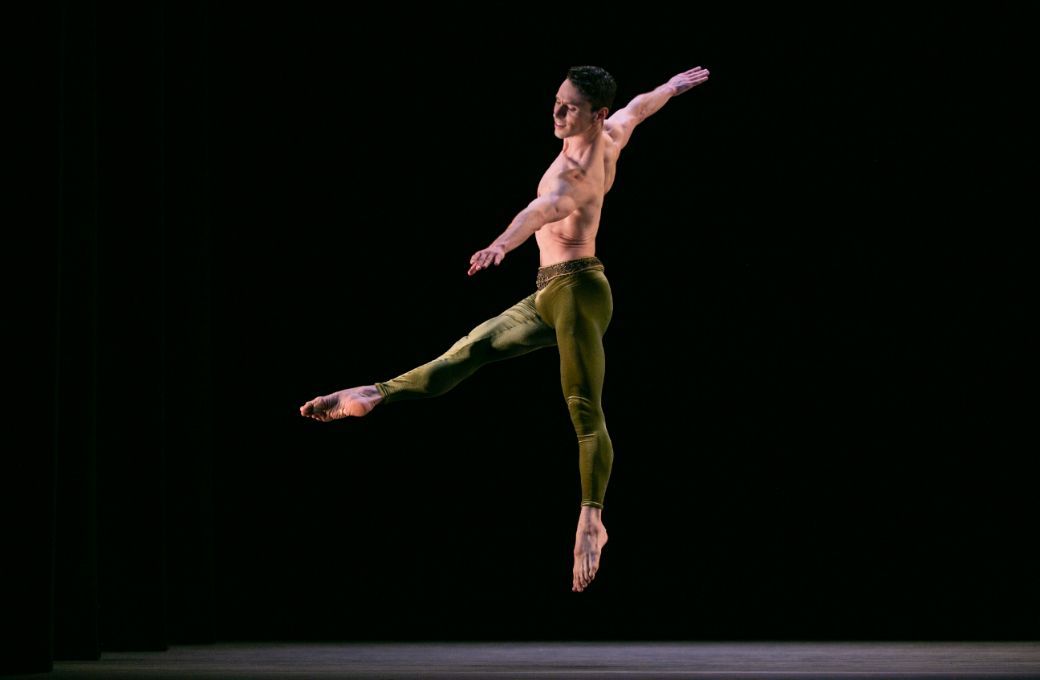

How the two groupings interact is inventive and allusions to Balanchine’s Apollo can be made in how the central man supports the three women. Given a solo of unusual, quiet intensity for a male dancer in Brandenburg’s fourth movement, John Harnage ravished in moving his limbs through space: an arm and leg in attitude derrière carving out different realms that resolve into a grand arc of his torso. The third movement is playful and richly varied, with moments of high drama that amplify the tension of Bach’s music with truly virtuosic rhythms in the dance phrases, all whilst displaying Taylor’s spatial authority in how the dancers intermingle. Of the three ‘muses’, Jessica Ferretti’s dance monologue here was lucid and magnetic. A piece of intense physicality despite its top-notes of ease and flow, Brandenburgs sits in a category of a dance-making craft many choreographers never reach.

Artistic legacy is a question of any genre and it’s felt weightily in dance. How the Taylor Company are forging forward whilst stewarding Taylor’s choreographies is to commission new voices, inevitably provoking a dialogue between heritage and where we are now. Perhaps unintentionally, Robert Battle – former artistic director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater – made a piece that called to mind Taylor’s own Company B, not in subject matter, but in the use of social dance and an architectural motif that sees featured soloists flanked by passing lines of fellow dancers far upstage.

As a tribute to his mother and the life-giving force of dance, Under The Rhythm is a riot. The dancers move as if manically compelled to, which is both exhilarating, but somehow sinister. Heavily influenced by jazz, an art form that sprung forth from the sounds and rhythms of slave songs and spirituals, Battle creates movements that arrest your attention for its tight unison and fizzing energy, but beneath our titters at some of the physical comedy, especially in a duet for Lee Duveneck and Alex Clayton, there’s a sense of unease: what is underneath this frenetic pace? In the way that Taylor’s Company B disguises the horrors of war, is Battle’s work showing the struggle that lies beneath a society’s efforts to live loudly?

The best dancers have a way to move with their entire being, not just their bodies, and it’s in Paul Taylor’s Piazzolla Caldera where we saw this to smouldering effect. Created in 1997, Taylor’s response to Argentine musician Astor Piazzolla and Polish-Jewish musician Jerzy Petersburshsky’s tango music is suitably raunchy, but it’s Taylor’s inventive use of patterns and groupings that intrigue.

Payton Primer and Kenny Corrigan were noteworthy for their physical commitment in an aggressive duet, whilst a sexually ambiguous quartet entitled Celos showed us four bodies aching for connection. Seen in conjunction with Brandenburgs, the evening’s closing work shows us Taylor’s curiosity, and his ability to translate emotion through music beyond the formal structure of any particular style.

As critic Arlene Croce illumined about Taylor’s work, a transparency between music and movement exists that identifies him as one of dance’s great classicists. Brandenburgs, with its sense of geometry, good manners and harmony even at moments of dramatic climax, most obviously displays this, but his ability to balance tone and physicality for theatrical effect shines in Piazzolla Caldera. You leave the theatre wanting to see more of the Paul Taylor Company dancers such was the ease of their stage personas, and hopefully 20 years won’t pass before we do again.