If you’ve watched the 2014 sci-fi hit Interstellar, you’ll know there’s a lot of intense conversations about gravity. Set in a dystopian future where astronauts journey into deep space, it turns out the Hollywood epic is excellent preparation for the contemporary dance double bill Skid/Saaba, by Swedish company GöteborgsOperans Danskompani.

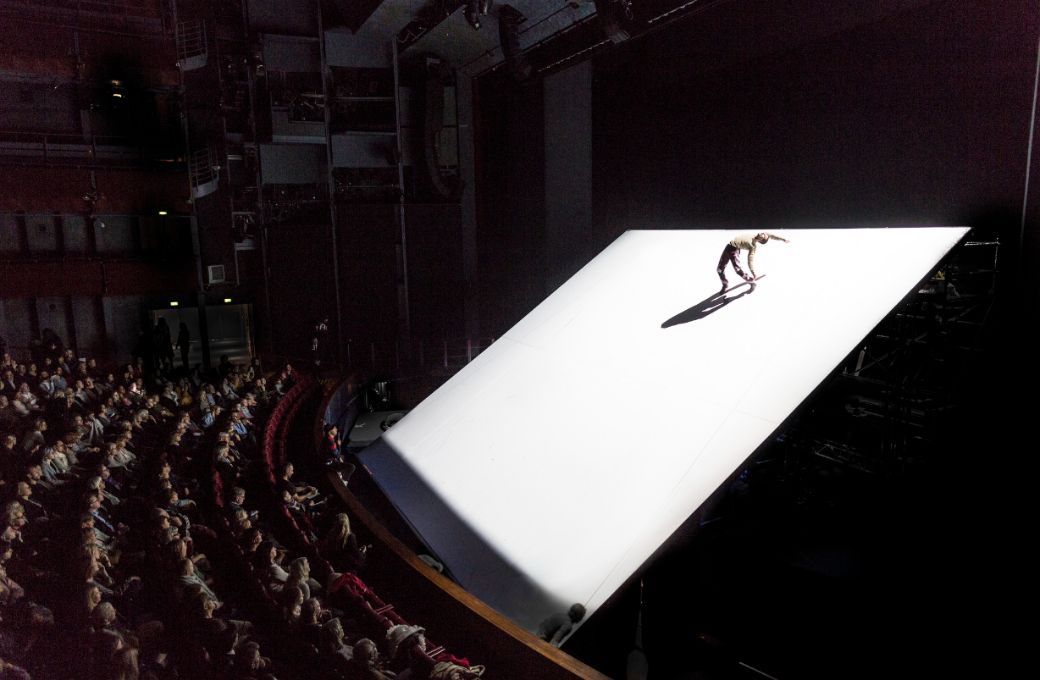

Speaking of cinema, let’s set the scene for Skid by Belgian/French choreographer Damien Jalet. Picture a massive, stark-white movie screen; now, tilt that screen away from the audience, until it’s laying at about a 35-degree angle. Next, watch a man crawl over the top, slowly assume a crucified position in the centre, and drift downstage. More bodies appear, sliding in heaped, contorted poses, and soft, cosmonaut cartwheels – it’s like the moment of chaotic silence after a mass casualty event, just before the sirens wail. Brace yourself as some of the dancers start to struggle against the gravitational pull; see them half-stand, knees bent, arms moving through quicksand in a “bullet time” windmill (it’s Neo from the Matrix during a galactic gunfight). Feeling dizzy, yet? Tense? You should be. This is the set for Skid, and it’s purposely disorienting.

One of the things that I love most about contemporary dance, particularly as a dancer who can’t truthfully list ‘grounded’ in my top five qualities, is the use of floor and its power. In your typical classical ballet, the audience won’t spend much time actively contemplating the stage floor, but those pirouettes and jumps that appear weightless can only happen because of the dancers’ intimate connection with the ground. Floorwork flips perspective and changes the bodies’ relationship with gravity; Skid masterfully takes this feature of contemporary dance and injects it with a hefty dose of steroids. Watching the dancers exhaust themselves against a brutal, inhospitable diagonal for 45 minutes left me with a vague sense of guilt for ever having taken a casual approach to being upright. You know when you’re falling asleep, and a moment of weightless panic snaps you back? Skid is that feeling. It’s a hypnic jerk of a piece, a feast of free fall while calculating impact force, and a kinaesthetic festival of gravitational feedback.

Given its slanted-stage premise, Skid could have slipped into one-dimensional territory. Thankfully, it’s saved from that, not only by the quality of its dancers and overall artistic intelligence, but the depth of its finale. After two acts of powerful ensemble contact work, Jalet chooses to finish Skid the way he started it: with one lone man. This time, he is rebirthed, strung aloft in the centre of the stage, in a womb-like cocoon. He emerges, and struggles up the middle of the diagonal, head down, back stooped, fragile, naked. Will he make it? Skid makes it worth finding out.

The second performance, Saaba, by Sharon Eyal, is also commentary on the dancers' relationship with the ground, this time by avoidance. Eyal has the performers tiptoe around on a Geisha-esque demi-pointe – a “floor-is-lava” type scurrying – for 90% of the piece. Like Skid, Saaba invokes the same sense of vicarious fatigue, watching the dancers refuse to succumb to gravity. Leaving the theatre, I heard a man, must have been an empath, exclaim, “I was exhausted for them because they were on their toes so much!”

Overall, Saaba is sultry, smoky and camp, with a hot, haute couture meets house vibe. It’s a bit like standing on the balcony of a Berlin nightclub, contentedly watching the beautiful people vibrate below. The dancers’ lacy, flesh-coloured body suits by Dior’s Creative Director Maria Grazia Chiuri certainly help. Along with the sexy, continental aesthetic, I would have attended this performance for the music alone: Ori Lichtik’s score journeys from crooning blues to throbbing techno beats.

In terms of the movement, it’s interesting when choreographers take classically trained dancers, with a superhuman range of movement available, and heavily confine them. Similar to structured poetic techniques (like a Villanelle, with its repeating stanzas and final quatrain), limiting options, if done well (and that’s a big if), can generate its own form of freedom and creativity. Just as using the right word, rather than the biggest, is true articulation, Eyal is a master of conveying delight in minutiae: the choreography in Saaba is full of quirky isolations, hand flourishes and pulsating torsos. Using sassy military salutes and salty petit jetés, the dancers parade diagonally across the stage, it’s armed forces meets Paris fashion week! There are also clear nods to Swan Lake, with parallel bourrées across the stage, and those iconic, undulating arms. However, given Saaba focuses so much on small, fast feet, but lacks the balance of longer, dramatic lines, the dancers constant demi-pointe ultimately reminded me of a Barbie in stilettos; the boundary between empowering and crippling is deceptively thin and it’s questionable which side Saaba ultimately falls.