Not long ago in a land not far away, a renowned ballet company announced an evening of new works on the theme of ‘woman’ to be choreographed by men. This provoked much eye-rolling and this-again-ing. The arc of power in the ballet world has since bent subtly toward parity with a few more women in the C-suite (Jaffe; Ferri; Watson) and more high-profile commissions going to female choreographers.

In this spirit, four dances made by women for men have just premiered at the Joyce in New York. Brainchild of the imaginative Daniil Simkin, who assembled a formidable cohort of his peers – Jeffrey Cirio (Boston), Osiel Gouneo (Munich), Siphesihle November (Toronto) and Alban Lendorf (Copenhagen) – and christened them Sons of Echo.

With the Greek nymph Echo recast as a creative mother-figure, living legend Lucinda Childs and ascendant choreographers Tiler Peck, Anne Plamondon and Drew Jacoby emerge as her avatars. Peck and Plamondon created new work while Childs and Jacoby retrofitted pieces for this crew. This Joyce run gives New Yorkers a rare chance to see five superb dancers up close, free from the classical repertoire that is the bread-and-butter of most men dancing at this level.

Comparisons to the early-2000s phenomenon Kings of the Dance are inevitable – Corella, Hallberg, Vasiliev, Tsiskaridze et al in a mishmash of gala variations and elevated kitsch. Sons of Echo is no reboot: even the name rejects aristocracy and roots the project in the feminine. Yet, like Kings, it trades on camaraderie, and when the choreography failed to ignite, the thrill of watching splendid technicians never dimmed.

The athletes were already warming up at barres onstage as the audience arrived, before launching into center routines set by répétiteur Tomas Karlborg. Fans who like to count pirouettes were on cloud nine. (I was there for the beaten jumps). An unexpected bonus: Maria Kochetkova bounded on in red basketball shorts and gave the men a run for their money – a daughter of Echo dispatching grand pirouettes like they did, the extended leg held firmly out to the side. The delightfully zany Karlborg kept up a showman’s patter, coaxing a longer balance here, a flashier finish there.

A reworking of Childs’ Notes of Longing kicked off the formal program. With a slimmed-down cast of four, it was short on the spellbinding abstract patterning for which she is famous. The bare-chested men in serenely billowing white trousers made the most of the minimalist choreography, winsomely gliding and scudding across the floor, occasionally reaching an arm skyward, or partnering another with a light touch. The music all but killed the vibe, though: at the piano, Vladimir Rumyantsev could wrest no drama from Matteo Myderwyk’s vapid, tinkling ruminations.

Tiler Peck provided a welcome jolt, unleashing Gouneo, Lendorf and Simkin on Gregory Porter’s jazzy “Real Truth”. Before Porter’s baritone was heard, however, the trio struck artful poses as a disembodied voice mused solemnly about “searching for the truth” – one of several spoken-word interludes by conceptual artist Monty Richthofen that crop-dusted the evening with platitudes.

Peck’s command of syncopation is a joy, and the dancers clearly felt it: rushing forward to hold a balance; tossing sharp accents into lush phrases. Simkin dazzled in a feather-light solo; Lendorf and Gouneo skimmed and slid across the floor in an elegant partnership. The dance revelled in the song’s jazz-soul groove but ducked the political urgency of lyrics written in 2020 when the world was on fire. Only during a rhapsodic Moog solo – when words fell away – did the choreography find its most exultant expression.

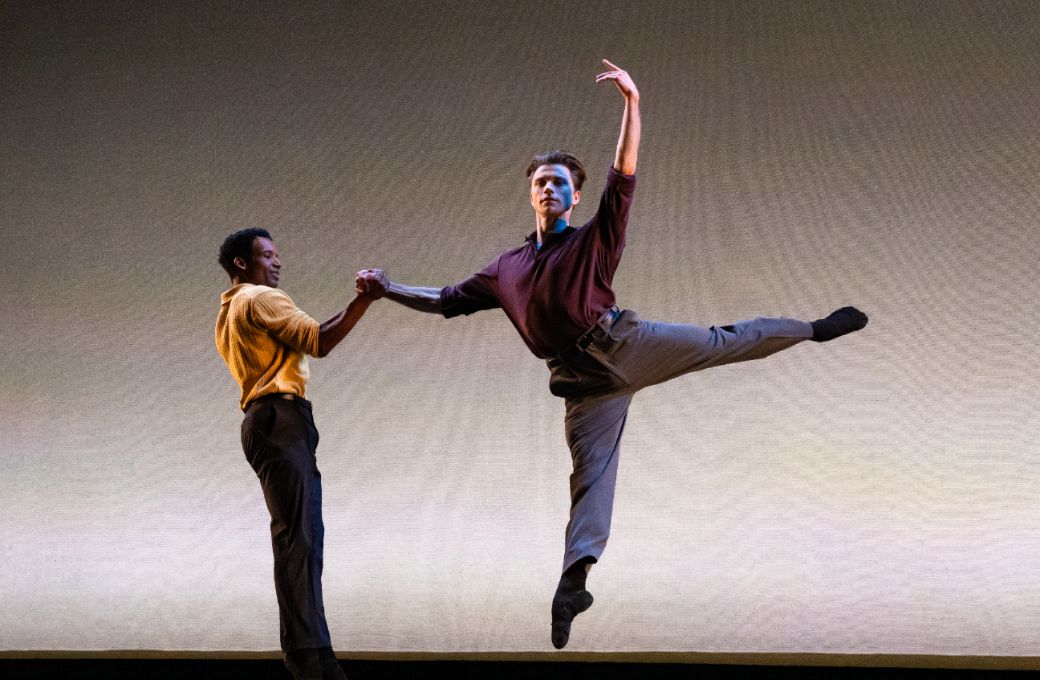

Anne Plamondon’s Will You Catch My Fall, danced by Cirio and November, unfolded to a cool original score by Ouri, all scraping electric strings. Trapped in smoke-filled beams of light, the men moved as if through viscous fluid, with liquid spines, their movement inflected with martial arts, popping and krump. A late barrage of spoken instructions proved mind-numbing, underscoring how much more eloquent the dancers were as they heroically supported one another through falls and recoveries.

Drew Jacoby’s Jack – the evening’s standout – was scored to battered Gershwin Preludes and scratchy, boomy, static-laden Futurist recordings: the analog world gone haywire. Clad in neon-dyed nylon-spandex, Cirio, Gouneo, Lendorf and Simkin glowered and toggled between bodybuilder flexes, voguing and catwalk strut. They reminded me of the gender-fluid incarnations of Captain Marvel. Cirio threw a tantrum and conducted an imaginary orchestra; Simkin unleashed ferocious isolations; Gouneo evoked Nijinsky’s faun, hands hinting at horns. Bravura ballet virtuosity slid delightfully into the mayhem. The only outbreak of spoken words were nonsense Dadaist syllables.

Ironically, this narrative-free evening was cluttered with words, mostly tired clichés (“a moment expands into eternity;” “admire the ones who didn’t ask permission.”) That, of course, was Echo’s fate: doomed never to articulate an original thought, only to parrot those of others.