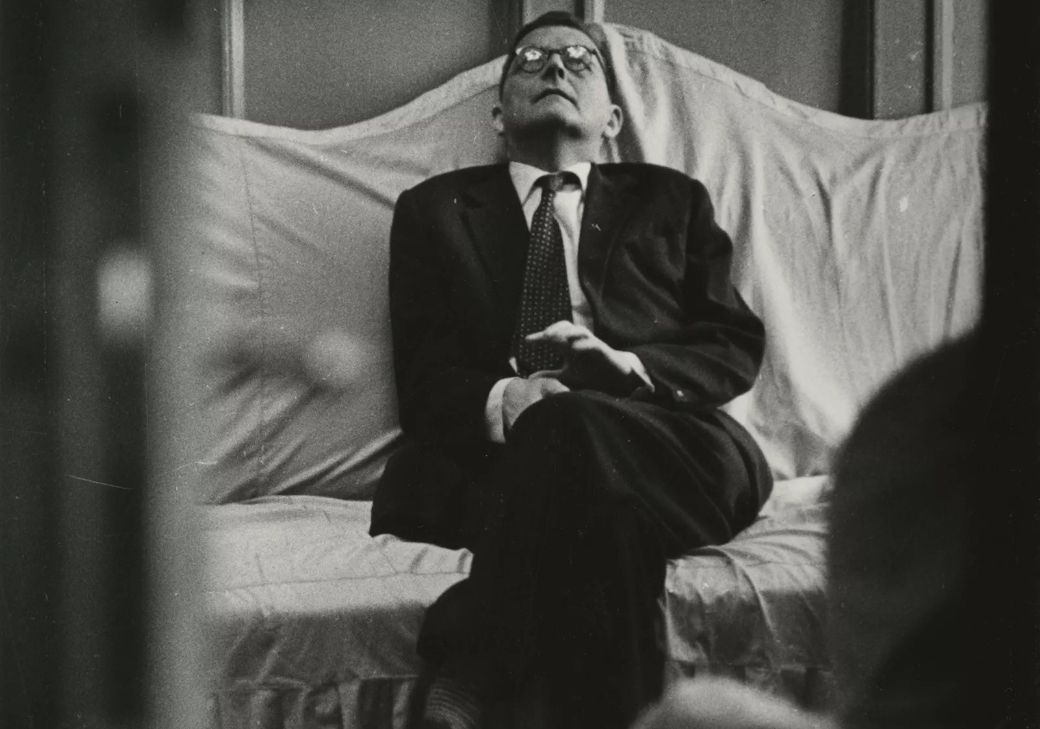

What does Dmitri Shostakovich’s music mean in our current moment? In May this year, I gave the English pre-concert talks for the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra’s mammoth cycle of Shostakovich symphonies and concertos, marking fifty years since the composer’s death. It was an overwhelming musical and emotional experience – one that I’m still trying to fully think through. Here are six things I learned in the process.

No frills

If you like fine decorative work, elaborate arabesques, or scintillating, seductive surfaces, then Shostakovich is definitely not the composer for you. The occasional little touches of glitter, like the harps in the trio of the Fifth Symphony’s Scherzo, are rare indeed. There are spellbinding colours and textures, but very often there’s an element of inspired ‘back to basics’ about them. It’s as if the orchestra’s primary colours are being rediscovered before our ears. How many other composers use widely-spaced divided strings with such directness as in the opening of the Eleventh Symphony?

Likewise, the Tenth Symphony’s first movement is almost virtuosic in its avoidance of orchestral virtuosity. First, we have low cellos and basses, but has anyone since Schubert made them sound so heavy with potential meaning? For the first two minutes we have nothing but strings, also mostly very low. Then in comes a single clarinet, in its weakest register – a pale light, but so welcome in the midst of Stygian darkness. Later on, a new theme emerges on low flutes – have low flutes ever sounded more weirdly ingratiating? Finally comes the desolate magic of the two piccolos intertwining above soft timpani rolls.

For Shostakovich, these musical occurrences aren’t just isolated touches of colour; each one happens at a key structural point: low strings (motto theme and introduction), clarinet (main theme), flutes (second theme), piccolos (coda and summation). Each sound is exquisitely placed and vital to the drama.

Structural mastery

The Tenth Symphony’s superb architectural strength didn’t come without a longish learning process. Shostakovich’s problem when he started out was that he just had too many ideas. A balance is maintained throughout the precociously brilliant First Symphony, but then, in the Second and Third Symphonies, thematic invention goes into overdrive. In the Third, after the relatively restrained introduction, things quickly become dizzying, like listening to someone in the throes of a manic episode, talking absurdly fast and flying off at tangent after tangent.

Hearing the Fourth Symphony after this is fascinating. Yes, it’s wild; sometimes the profusion of ideas pushes the frame near to bursting point. Yet now we can also feel connections, links being forged, not just from section to section, but across the MC Escher-like conflation of different forms. There are ropes across this abyss.

Next comes the tighter integration of the Fifth Symphony (Bach and Beethoven key models), and still more in the Eighth, showing as Aristotle once argued that expressive power can be enhanced by concentration, sustained sense of purpose, economy of thematic means. In tandem with this goes Shostakovich’s wonderful flair for creating very long, continually evolving melodic lines. The orchestral song that starts near the beginning of the Eighth doesn’t come to rest for nearly five minutes. And the first movement of the Tenth is like one great melodic arch. We are picked up by the cellos and basses at the start, then gently brought back to earth by the piccolos at the end. Intellectual means and emotional power are perfectly fused.

Sometimes structure doesn’t matter

There’s no point in denying it: symphonies like the “Leningrad” (No 7) or “The Year 1905” (No 11) are a lot looser, formally speaking, than Nos 5, 8 and 10 – or even No 4. In other works, too, some of those characteristic long solo instrumental recitatives, if they’re not performed with complete conviction, can lapse into distracted doodling. Given the same kind of half-hearted approach, the Leningrad and Year 1905 can be uncomfortably reminiscent of Henry James’s description of the novels of Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky: “loose and baggy monsters”. James has a point, yet at the same time, he doesn’t. War and Peace is a towering achievement despite the protracted philosophising, and The Idiot grips and shakes the soul even when one notices the loose ends, the plot holes.

What the Leningrad Symphony and The Year 1905 show us, when played and directed with understanding, is what a master of musical narrative Shostakovich was. As a storyteller, he’s up there with Mahler. Looking at the score of the Leningrad, I’ve tut-tutted at the starkly clichéd horn and timpani fanfares near the end of the first movement. But hearing them in Leipzig, with a captivated audience, was like listening to an account of an epochal event related by someone who falters occasionally, who may lose their thread for a moment here and there, but who speaks with such urgent immediacy that you just don’t care. Of course, knowing the background story helps, but how many pieces of music, honestly, do we approach with absolute purity of aesthetic intention? (The Art of Fugue perhaps…)

I / We

Mahler is perhaps the greatest self-dramatizer in all music, in the sense that in searching his own soul, his own personal history, he finds truths we can all relate to. But there is a huge amount of self-exploration, of personal catharsis, in Shostakovich too – especially in the string quartets.

Yet as with many great Russian artists before him, there is a powerful sense of shared experience. The image of ‘the people’ carried an enormous emotional charge in Russia long before it was co-opted by the Bolsheviks. When Shostakovich invoked the tragic ‘people’ theme from Mussorgksy’s Boris Godunov in the Tenth Symphony’s white-water-rage Scherzo, he did so knowing that most of his audience would recognise it, and that it would inform their response to the whole movement.

But you don’t have to be Russian to hear the recurring echoes of Russian folk song and dance, of Jewish Klezmer music in the First Violin Concerto, or the ritualised chant-and-choral-responses at the beginning of the Leningrad Symphony’s third movement or at the heart of the Fifth Symphony’s great elegiac Largo. At the end of the Leningrad, the return of the opening ‘city’ theme, bloodied, scarred but unbowed, at the end of the Finale, now sounded by an offstage chorus of ten brass instruments, is a clear communal cry of ‘We will survive!’

So too is the pounding, high-kicking D-S-C-H (the composer’s musical ‘signature’) at the Tenth’s conclusion: a half-desperate, half-ecstatic shout of ‘I’m still standing!’ And then there’s the way the muttering bass clarinet sets off a full-orchestral riot of defiance at the end of the Eleventh – one voice initiates and merges with the voice of the many.

The Cold War is over

Where was Shostakovich’s true loyalty? Was he really a Communist? Was he really a dissident? The days of slanging matches over such questions seem (thank God) to be drawing to a close. As anyone who’s read Nadezhda Mandelstam’s phenomenal Hope Against Hope will know, people living under such all-pervasive repression as in Stalin’s USSR survive partly by refusing to ask themselves such questions.

Is the end of the Fifth Symphony a vindication of Socialist Realism or a noisy outpouring of embittered irony? The answer is, probably both – and more than that. Surviving in what often seemed like a nightmare version of Alice in Wonderland often meant being able to field brutal absurdity, or a kind of self-splitting that goes beyond ‘masks’ and ‘real faces’.

The arguments over Shostakovich’s politics – and the politics of his music – have also obscured that he was very much a human being. Many of the codes and allusions that speak most unambiguously have to do with women Shostakovich was in love with. Strenuous efforts have been made to explain the self-quotations in the Eighth String Quartet, but one big thing they have in common is that they’re all works that were huge successes at their premieres – and what else would one expect from a work allegedly “dedicated to the memory of myself”?

When the music does raise its voice in grief and fury, there may be no need to worry too much about which specific events Shostakovich had in mind. Its applicability is more general. To us, today, this music can offer the comfort and encouragement of magnificent, thrilling, shared expression. As a Russian I met long ago put it, “There’s something about hearing your most painful feelings transformed into something beautiful…”

Sometimes he just likes playing with us

Listening to people who knew Shostakovich and worked with him, hearing stories of “what Dmitri Dmitriyevich told me” about this theme or that detail, I’ve struggled with the subversive suspicion that Shostakovich was often winding them up – or at least telling them what they wanted to hear. Even if you believe Testimony, there are still good reasons for keeping that grain of salt close to hand. Shostakovich was a wonderful, barbed humourist. As with many Russians who survived Stalin, it was almost certainly a sanity-saver.

But what was he laughing at? After the Eighth Symphony’s final soul-scouring climactic outpouring, in stumbles a chuckling, gurgling bass clarinet and a clearly inebriated solo violin. It’s vividly reminiscent of the moment in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment when, just as the detective Porphyry is salivating at the prospect of Raskolnikov admitting to the murder, a drunken peasant lurches in and confesses to the whole thing.

And what about the famous quotations in the Fifteenth Symphony? “I don’t quite know myself why the quotations are there, but I could not, could not, not include them”, he told close friend Isaak Glikman. Just try unpicking those multiple negatives for a moment. Perhaps these are just reminders that life is absurd – or that if there is an ultimate sense to it all, we lack the tools to understand it.

Commentators argue about the ending of the death-obsessed Fourteenth Symphony. Is he protesting against unjust killing? Is he trying to remind us that life is precious? Or could he – really – just be having fun frightening us? And that last-minute major key bell-sound at the end of the Fifteenth – after all we’ve been through in this symphony, the clink of a vodka glass and the hint of a wicked smile: Go on – make sense of this then!

See all upcoming listings of music by Dmitri Shostakovich.