Something about Idomeneo seems to stump directors. Mozart's first mature opera, written for the Munich court in 1781 and representing the young composer's enthusiastic response to the Gluckian operatic reforms, undoubtedly has its challenges: the movement of the prominently present chorus and the appearance of a sea monster are not easy to stage. But its subject material itself, focusing on the aftermath of the Trojan War, is hardly out of operatic bounds: a tale of the traumatic aftermath of war, of love versus duty, of human selfishness and sacrifice. And yet Kasper Holten's production at the Wiener Staatsoper joins a long line of stagings that struggle to get a good grip on the dramatic material.

It's hard to define Holten's concept. The staging traces Idomeneo's descent from warring king to reviled, psychologically broken, and unceremoniously deposed tyrant, but it does so all too vaguely, evidently unsure of whether Idomeneo, the unraveling ruler who ultimately poses the only menace to his people, is a detached psychopath or an unfortunate, traumatised man.

This ambiguity is compounded by distinctly, frustratingly undramatic direction. The characters' interactions (or the lack of thereof) often undermine both text and relationships: a representative early example is Idamante's love confession Non ho colpa being declaimed with his back turned to his beloved Ilia, who, in turn, is concerned with everyone but the yearning prince. The static, colorless treatment of the chorus drains all life of the opera's grand scenes, and the score's editing and rearranging mars both music and action. The Act III confession and love duet between Ilia and Idamante being moved to the beginning of Act II outright destroys the opera's dramatic structure, a blunder worsened by letting the original action proceed more or less untouched. The Idamante who obeys his father's order to leave Crete with Elettra not before but after he's learned that Ilia reciprocates his love comes across not as tragic, but spineless. Muddled affections reign elsewhere, as Idomeneo seems more interested in Ilia than the fate of his son, and the emotionally overcharged Fuor del mar, nominally a tortured reflection on his selfish vow endangering the life of his own son, explodes after Ilia rejects his advances. Elettra's humanity and genuine affection for Idamante is perhaps the only aspect where the staging strikes right, enabling a more three-dimensional portrayal of the often maligned character.

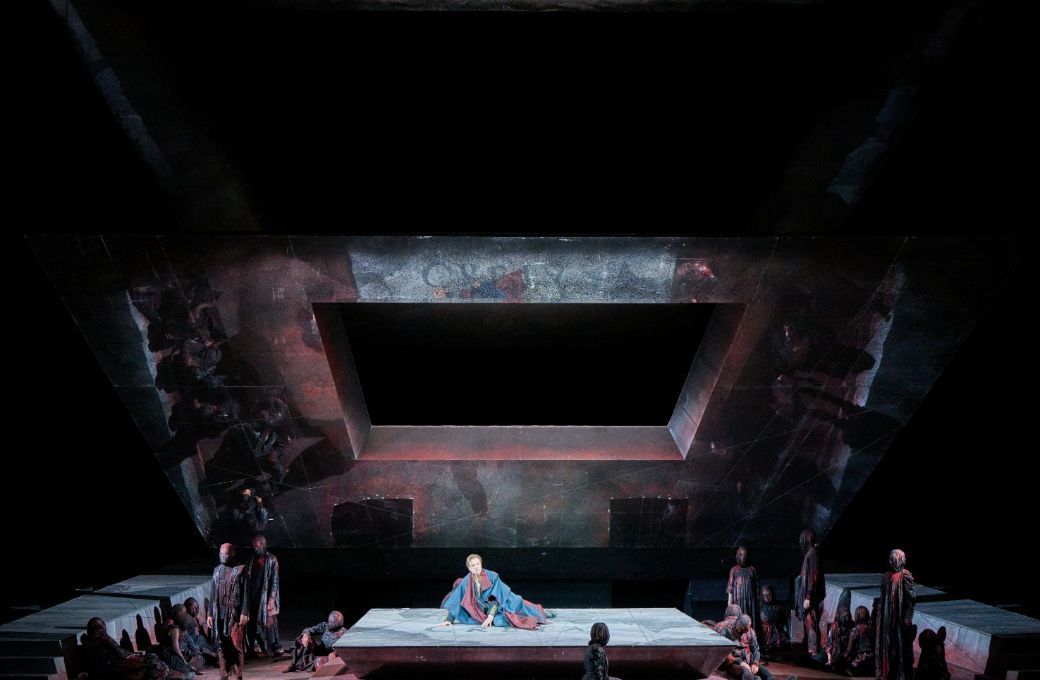

Scenically, there is little to spark interest or aid the performers. Mia Stensgaard's sets, a grey, multi-level structure that opens up like a leaflet, has appealing elements (the map of the Mediterranean, where the main characters' figurines are moved around like strategic board pieces, its bloodied underside where Idomeneo first reappears), but its use feels rather underbaked, and the open sides are not particularly singer-friendly. Anja Vang Kragh's stylized, vaguely early 19th century costumes work best in Idomeneo's blood-stained court dress, and are largely nondescript elsewhere.

Musically, the performance was thankfully of a considerably higher quality, if the cast could never really overcome the dramatic inertness. In the title role, Bernard Richter's clarion tenor offered a regal enough tone, but the cavatina Accogli, o re del mar is where he is most comfortable in the role; the bravura aria Fuor del mar was valiantly attempted rather than accomplished. Kate Lindsey brought expectably lively acting to Idamante, and her burnished timbre and expressive vocal coloring charmed aplenty, though her mezzo is palpably of a smaller scale. Her Act II showpiece, Non temer, amato bene, borrowed needlessly from Mozart's 1786 revision, didn't sit quite congenially on her voice. Ying Fang's round, supple tone and limpid voice made for an ideal Ilia: despite the occasionally some uncertainty in the upper register, Se il padre perdei and Zeffiretti lusinghieri were enchantingly sung, and the accompanied recitatives all eloquently delivered. Eleonora Buratto's warm-toned Elettra was highly sympathetic, impressing with vivid, sensitive phrasing: vocally darker and more vehement, she provided suitable contrast with Fang's Ilia, though a little more bite might have been welcome in the commendably sung Tutte nel cor and D'Oreste, d'Ajace.

Bertrand de Billy seemed determined to drive through the opera at breakneck speed. If, at the beginning, this resulted in messy articulation from the strings, ultimately it also ensured a tightly paced, dramatic, stylish reading, lending back a little of the work's thunderous thrill that the staging so dampened: O voto tremendo was particularly memorable with its striking darkness, while the four-part obbligato of Se il padre perdei was rendered with ravishing beauty. The chorus' contributions were not entirely electrifying, but always thoroughly respectable.

You couldn't describe Idomeneo's run at the Wiener Staatsoper as glorious, with barely 90 performances in the house's nearly 160-year history. With Holten's staging, it would certainly be hard to convince the Viennese public that Mozart's masterpiece does deserve a place in its repertory.