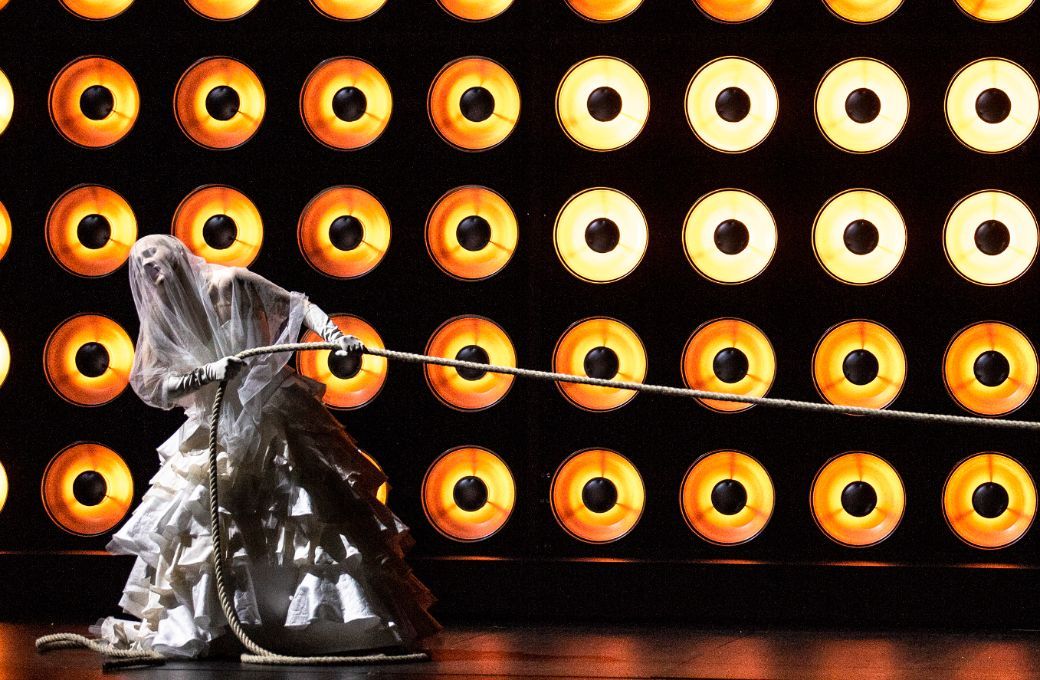

Any new production of Tristan und Isolde – the ultimate Wagnerian love story – is, by definition, an event. So it proved once again at the Deutsche Oper Berlin where Michael Thalheimer’s production received its premiere. From the first bars emerging out of silence, the void on stage mirrors the music’s metaphysical beginning: out of total darkness, a wall of circular lamps begins to flicker and shimmer, lighting Isolde’s path. She pulls on a long rope – perhaps symbolic of her past, which she soon recounts in her long monologue – and finally collapses, exhausted, centre-stage. The image returns in Act 3 when Tristan drags a similar rope behind him, on his way from this world to the next.

Thalheimer’s approach sublimates the lovers’ passion into a world of thought and memory. They scarcely touch, their ecstasies confined to the mind. His collaboration with set designer Henrik Ahr results in a stripped-down aesthetic of stark, almost monastic minimalism, dominated by a light installation of 260 spotlights, symmetrically arranged and carefully synchronised with the action. The otherwise bare black stage depends entirely on this play of light: when total darkness falls during the long-awaited night of love, or when all the lamps light up in the cold dawn of “der Öde Tag”, like searchlights at König Marke’s sudden entrance, the visual impact is undeniable. Yet despite these moments of brilliance, the static tableaux and absence of genuine human interaction leave a vacuum of emotional tension. One could imagine the work presented in concert form; at least then the austerity would seem intentional rather than inert.

Musically, however, the evening rose to far greater heights. Soprano Elisabeth Teige, making her role debut as Isolde, cut a strikingly beautiful figure and grew in vocal assurance as the evening unfolded. Her youthful, silvery soprano gained in suppleness and amplitude, though in the Liebestod she was occasionally overpowered by the orchestra. It cannot have helped that she was asked to sing, quite literally, with a slit throat. Dramatically, her longing for Tristan remained an idea rather than an experience, a limitation more of the staging than of the singer.

As Tristan, Clay Hilley offered heroic stamina and presence, if not the most alluring timbre. His tone could turn metallic, yet his charisma and musicianship were never in doubt. Still, the production’s emotional frigidity constrained him, even though Thalheimer had him and Isolde cut their wrists during the apotheosis of the love duet in the second act. This felt sudden and unmotivated, at odds with the music’s emotionality.

The supporting cast anchored the drama with welcome authenticity. Georg Zeppenfeld, arguably the finest Marke these days, brought grave dignity and immaculate diction to his great lament. Thomas Lehman’s warm, resonant Kurwenal was a revelation, his first phrases already commanding attention. Irene Roberts, a thoughtful and richly voiced Brangäne, sang with compassion, while Dean Murphy’s taut, nervy Melot – dressed in an ominous yellow suit – radiated barely suppressed jealousy.

At the centre stood Sir Donald Runnicles, leading his orchestra in a reading of exceptional unity and depth. From the first breath of the Prelude, he shaped Wagner’s vast structures with natural flow and luminous transparency. The woodwinds, often heartbreakingly tender, were given space to sing, the bass clarinet weaving dialogues of haunting intimacy with Zeppenfeld’s Marke. Coordination between pit and stage was excellent, even with the chorus (prepared by Jeremy Bines) positioned behind the set. The offstage horns in Act 2 played with remarkable precision, and special mention must go to Chloé Payot for her plaintive cor anglais solo and Martin Wagemann for his radiant trumpet in the final act, both deservedly applauded.

With this Tristan, Runnicles marks the beginning of his farewell as General Music Director. His first Wagner premiere at the house, Graham Vick’s Tristan in 2011, had already revealed his instinct for atmosphere and architecture. Fourteen years later, he leaves behind an orchestra at the peak of its expressive power. In this production’s stark void, it was Runnicles and his musicians who supplied what Thalheimer withheld: passion, tension and transcendence.