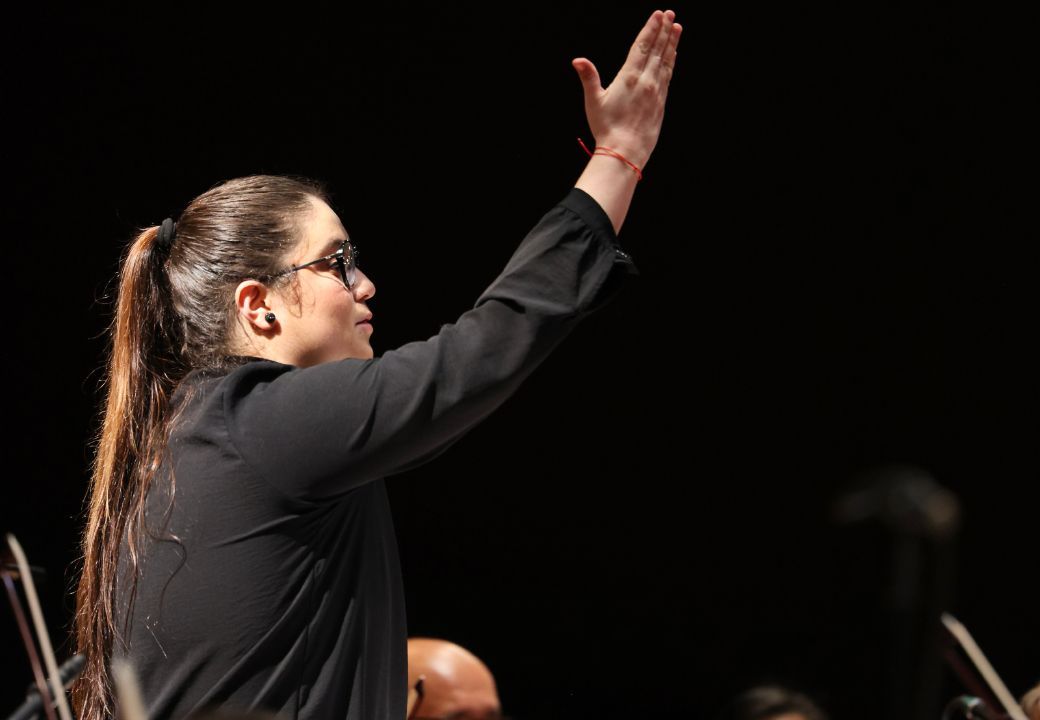

A journey that began with waving her grandmother’s knitting needle has brought Ana Maria Patiño-Osorio from her small Colombian town to Geneva, and the assistant conductor’s post of the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. That journey is emblematic of a rapid evolution in the origins of new-generation conductors, their career paths and opportunities, but it’s also a personal story of remarkable tenacity, determination and love for music.

In an online chat from her flat in Geneva, Patiño-Osorio pays warm and selfless tribute to her parents. She was born in 1995, the eldest of three children, in La Unión, 60km south of Medellín. “We lived on a farm, so my father would get up very early to work, and by 6am I would already hear him singing away with his coffee. He is still like this! He wanted to give us the best possible education. My parents didn’t have much formal education, though they are very smart and intuitive people, but they were very poor when they were young, so they wanted us to study and to make the best of ourselves. The house was filled with books and movies and music. Ever since I can remember, music was part of our lives.”

In modest surroundings, Patiño-Osorio and her siblings were shielded as far as possible from the murderous turmoil of Colombian politics in the 1990s. “In these small towns in Colombia, guerrilla gangs affiliated to FARC were kidnapping and killing people, and this happened to many members of my extended family. My parents suffered so much, but they tried to keep us in a bubble of love and science and literature.”

Collective music-making in Hispanic countries centres on wind-bands, and Patiño-Osorio rapidly discovered an aptitude for the saxophone. Even at the age of eight, though, she was being encouraged towards a career in music by the band’s conductor, Jhon Jairo Martínez. In rehearsals, she found herself paying closer and closer attention to the music beyond the notes on her own page. “I started to learn the pieces we used to play as if I were the conductor. I wasn’t looking at my score anymore, I was just looking at him.”

One day, Martínez had to break off mid-rehearsal to take an urgent call, and you can guess what happened next. “He just looked over at me and said, ‘Please take over – I have to go.’” Patiño-Osorio stood up, in front of her friends in the band, and let intuition take over. Then she pinched a knitting needle from her grandmother’s house, and began to practise at home, listening all the while to her father’s cassettes, guided by her ears and her emotions through pieces like Brahms’s Third Symphony. “At a very early age, I realised that this music made me so sad. Now that I have studied Brahms so much I get it, but when you are five years old and listening to the slow movement of this symphony you are so touched. Many pieces were just too much for me to take. They made me feel too much.”

Success in a national competition – on the saxophone – won Patiño-Osorio a scholarship to study at the Universidad EAFIT in Medellín. At 16, she left her family bubble to live alone in a flat in the city. “It’s not like my parents could accompany me: they were working and looking after my brother and sister. My mother is a strong woman who has been through a lot, and she told me, ‘You have to do this’. They trusted me.”

The learning curve was steep – Patiño-Osorio had scarcely heard a violin live, let alone studied a full score: “It was really scary at the time.” But her saxophone studies were soon fitted around an obsession with orchestras. “I used to play all the time: salsa, Latin jazz, all kinds of styles. And suddenly I realised that I had to study string instruments from scratch. I had no idea how they worked – what the difference between an up and a down bow was, why you should play with one fingering and not another. So I began to ask all my friends to explain it to me.”

Colombian conductor Alejandro Posada, chief at Castilla y León Symphony Orchestra and founder of the Iberacademy mentorship programme, has played an instrumental role in cultivating orchestral culture in Colombia over the last 20 years. (His influence is similar to that of José Antonio Abreu, founder of the Simon Bolivar Youth Orchestra and El Sistema in Venezuela.) Posada took Patiño-Osorio under his wing, and she switched diplomas from saxophone to conducting, completing her degree in three years so that she could embark on a professional career as soon as possible.

When not otherwise engaged on her accelerated study programme, she made herself useful with the orchestras in Medellín: “moving chairs, writing programmes, hanging around rehearsals. I did everything I could, just to be there, to ask questions of the visiting conductors, maybe get five or ten minutes with the orchestra. And when times are difficult now, when I feel stressed about learning a new piece with a tight deadline, I try to remember those days, and that feeling of simply being happy to be there.”

One of those guest maestros was Andrés Orozco-Estrada, Medellín-born but based in Vienna since 1997. He, too, recognised Patiño-Osorio’s talent, and invited her to become his assistant at the Filarmónica Joven de Colombia (Colombian Youth Philharmonic). Having won a place on the conducting programme at the Lucerne Festival Academy – associated from its inception with Pierre Boulez – Patiño-Osorio travelled to Europe for the first time. “This was huge news for me. I have another mentor, Roberto González-Monjas. He wanted me to go to Europe and study but I didn’t have any idea how. When I got the place, I remember my father going crazy, shouting through the house – it was like a dream for me.” In Lucerne, she was coached by Bernard Haitink. “He was very kind. And he told me, ‘You really should come to Europe to study. Think about it.’”

Having completed her studies in Medellín, she returned to Switzerland, securing a much-prized place on a Masters course with Johannes Schlaefli. Young conductors once worked their way up the ladder in an opera house, coaching singers, playing for rehearsals, conducting off-stage ensembles. Such posts are now rarer than ever, time spent in front of an orchestra is golden, and it is competitions and fellowships that offer a start to Patiño-Osorio and her colleagues. What they make of that start is up to them. “As a conductor at the start of your career, you have to face the human side of the job. With a challenge like problems of communication, you cannot study it, you have to learn with experience. And we need time with repertoire: to feel it, to talk about it. You have to do a piece to learn how it goes.”

Orchestral musicians are not renowned for their patience. They make up their collective minds about a new conductor in 30 seconds, sometimes less. “It’s normal for many orchestral players that they don’t trust a young conductor immediately. They need to see if you can do it.” Persuasion does not always work. “But a big part of my personality is that I take failure as input. I suffer a lot inside, but I grow a lot from these experiences. And I have other – what to call them? – qualities that I bring. One that I am Latina, another is that I am a woman. I’m always telling myself, no one is going to tell me that I cannot make a success of myself because of this or that. I just feel a huge responsibility to do it.”

Assistant conductor posts don’t always work out, as Patiño-Osorio knows: “What if I spent two years just sitting listening to rehearsals?” Happily, her time with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande has proved far more fruitful. Getting up close with the rehearsal methods and techniques of contrasting guest conductors has been rewarding in its own right: “Charles Dutoit, and then Daniele Gatti and then Daniel Harding – they’re all amazing, but so completely different from each other.”

Better still has been the time spent working and talking with the OSR’s Music Director, Jonathan Nott. “We both have a special connection with Mahler. But when I see him doing Mahler’s Ninth, and then I see him doing Ligeti, I don’t see a big difference in his approach. He always wants to tell a story, and he always talks about emotions, human emotions, in the music. And so whether I’m preparing Schumann’s Third or a new piece by Michael Jarrell, I have learned from him to go deep into the score and find the emotion. And we have spent so much time discussing the music in its context, especially with Richard Strauss: Cervantes and Don Quixote, for instance, or Stefan Zweig and the Four Last Songs.”

Another lucky break came in January 2023, when Patiño-Osorio replaced Alondra de la Parra at the last minute and won a glowing review from the Swiss newspaper Le Temps. The opportunity to work – at speed – with Mikhail Pletnev on Ravel, and with Daniel Lozakovich on Saint-Saëns, was valuable in itself, but the concert also brought her to the attention of agents and other orchestras. Her ambitions, though, do not centre around a debut with this or that venerable institution: her focus is trained on the music, learning more of it and taking a lot of it back to Colombia, where she has retained close connections.

“Did you know,” she asks me, “there are pieces like Mahler 3, Mahler 8, that have never been performed in Colombia? To make that happen: that is what I would really like to do. I want to go back: not necessarily to live there, but to share and give back everything I have learned. In Colombia, we have more and more musicians who go to Europe or the USA or Asia to study or to play. Many of them are making wonderful careers, like my teachers, and they are opening up so many possibilities. And suddenly you think to yourself, I'm also from Medellín. So I could do it.” Nothing in life is certain, but with Patiño-Osorio’s determination, anything is possible.

See all upcoming performances by the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.

This article was sponsored by the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande.