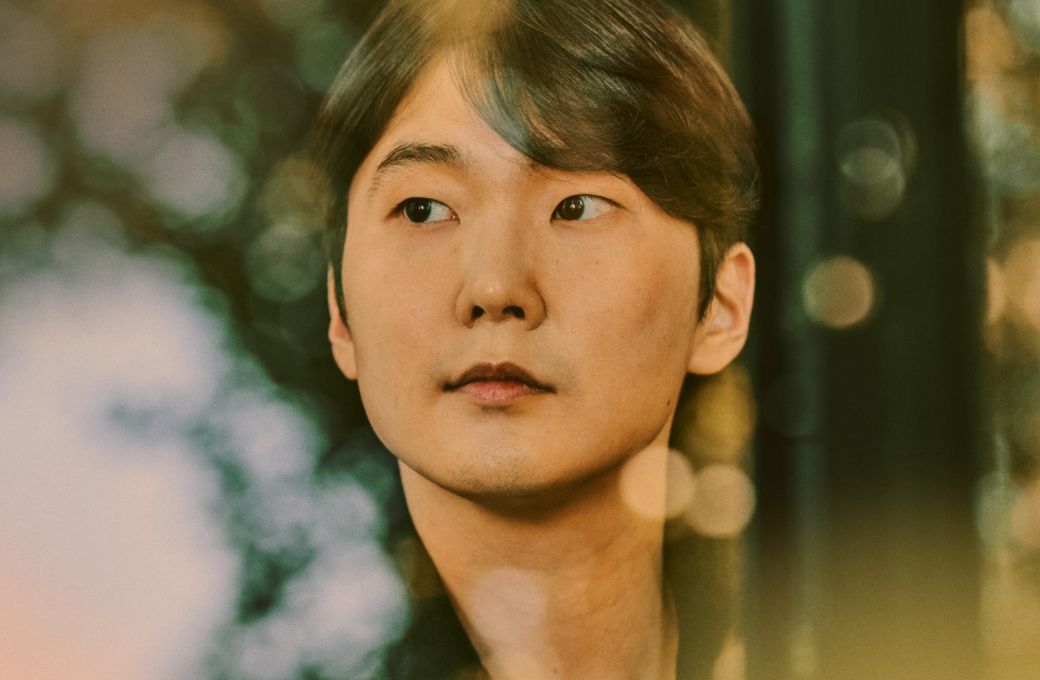

Seong-Jin Cho has been immersed in the music of Maurice Ravel more than most pianists in this 150th anniversary year of the composer’s birth. He recorded the complete solo piano music for Deutsche Grammophon, performing it in more than 20 ‘Ravelathon’ recitals at venues from Carnegie Hall in New York to London’s Barbican. He’s also performed and recorded Ravel’s two piano concertos and, this autumn, returns to the G major concerto to launch the Czech Philharmonic’s season, before they take it on tour to Japan and Taiwan.

“Ravel’s works are a highlight of the piano repertoire, full of imagination,” the softly spoken Cho tells me when we meet at Steinway & Sons in London. “My first encounter with Ravel’s music was the Alborada del gracioso from Miroirs when I was 12 years old. At that time, my impression about Ravel – or French music in general – was that it was very mysterious, kind of blurry with lots of pedalling. More pedals than motor! But after studying with Michel Béroff, my perception of Ravel’s music totally changed.”

Cho studied with Béroff at the Paris Conservatoire. “I played all of Ravel’s music for him. Michel was not only a great teacher, but also a great pianist himself, so he was able to demonstrate. It was so fascinating to witness his interpretations.” When asked which other pianists he listened to when studying Ravel, Cho picks out Marcelle Meyer and Walter Gieseking from the early 20th century and, among contemporary pianists, Louis Lortie and Jean-Yves Thibaudet.

We compare Ravel’s meticulous writing with Debussy’s. “Ravel was very academic in a way. His music is very orchestral, very different from Debussy’s music. There is more fantasy in Debussy, more room for interpretation. But Ravel really knew what he wanted. After performing these complete piano music recitals, I realised that he was a real genius. Everything makes sense. He really knew the instrument so well. Even though much of it is so difficult to play, somehow it just works.

“And it sounds so orchestral. I always try to indicate some specific instrument, like an oboe, for example.” Many of Ravel’s orchestral works, of course, started out originally as piano scores.

“I think the Toccata from Le Tombeau de Couperin is one of the few very pianistic pieces. You cannot orchestrate this.” Indeed, Ravel left out the Toccata (and the Fugue) when orchestrating Tombeau, although that hasn’t stopped Kenneth Hesketh and David Molard Soriano from orchestrating it recently.

What was the experience like for Cho, immersing himself in these Ravel marathons? “The final recital happened last month in Aspen,” he explains, “and I was hoping that I’d get used to this programme, but I’d still be exhausted after the performance. There were two intermissions, so about three hours in length. It was still fulfilling, with each evening like a journey.”

Cho sequenced the works chronologically, so I asked whether he could see a development in Ravel’s piano writing?

“Maybe not a development, but changes, yes. His early music was very influenced by dance: the Sérénade grotesque, Menuet antique. The Pavane pour une infante défunte is, of course, dance music too. Then he moved to Jeux d’eau and the Sonatine, smaller pieces, before Miroirs and Gaspard de la nuit, which I think are highlights of his piano writing.” Cho uses his hands to indicate a peak. “And then he returned to dance music again, the Valses nobles et sentimentales and Tombeau de Couperin – back to Baroque dance – but in a different, more mature style. A newer story influenced by Baroque – and maybe Schubert in the Valses – but mainly Baroque.”

Which is the most challenging to play, I ask. Scarbo from Gaspard, which Ravel wrote to outdo Balakirev’s finger-crunching Islamey?

Cho grins. “If you don’t have a good piano, Scarbo is challenging! It’s not possible to play the repeated notes. But for me, Miroirs is more difficult: five varied pieces in a row without interruption.”

When it comes to the concertos, Cho recorded them with the Boston Symphony – still probably the most ‘French’ of American orchestras – and Andris Nelsons. They were reunited at Tanglewood in July where Cho played both concertos in the same concert. Apart from the obvious – the D major being written for left hand alone – how do their styles differ?

The Left Hand Concerto is the more complex music, in my opinion. It reminds me of war, very dark, but in between it’s very jazzy and the piano theme is very nostalgic. It’s very complex and compact music. While the G major concerto is also jazzy, the Adagio assai is the highlight, one of the best second movements of any piano concerto in history. I can feel the mature Ravel here, in a major key [E major], but very, very sad. It’s nostalgic, sentimental. I always imagine a person who is smiling, but there are tears in his or her eyes.”

Cho reveals that he first studied the G major concerto at the age of 15 with Myung-whun Chung. “We’re still performing together. I learn so much from him. He’s kind of my mentor. He was a great pianist himself, so he knew what I was doing. He knew everything. He heard everything. So after the rehearsal, he would sometimes give me some comments.”

In September, Cho plays the G major with the Czech Philharmonic and Semyon Bychkov in Prague’s Rudolfinum, before touring it. He made his debut with the orchestra two years ago with the world premiere of Thierry Escaich’s Piano Concerto, “Études symphoniques”.

“They instantly became one of my favourite orchestras in the world,” Cho explains. “They are fabulous, but somehow very underrated. They have such a special string sound, not only in the Escaich concerto, but in Petrushka in the second-half when I was in the audience, which was fantastic, one of the best Petrushkas I’ve ever heard. Maybe it was because of Maestro Bychkov, but they sounded really great. I’m really hoping that we will collaborate very regularly in the future. And they have a fantastic hall too!”

Cho is one of a young generation of Asian pianists – along with the likes of Mao Fujita and Yunchan Lim – who are idols to adoring fans, particularly in Cho’s native South Korea. How does Cho explain the popularity of classical music there, where the young fan base is enormous, especially compared to Europe?

“I think the age of the Korean audience is significantly younger than the European audience. I have been asked this question many times before, and I was thinking about why. Maybe because Korean people don’t have a long history of classical music, compared to Europe, we are more open-minded. We don’t think that classical music is only to be appreciated by older people. Young people appreciate K-pop or classical music equally. Of course, K-pop is more popular but classical music is not just an ‘old thing’ for the Korean audience.”

Cho shot to fame when he won the Chopin International Competition in 2015, but, despite the inevitable interest, he was successfully dodged being labelled a Chopin specialist. “Being a Chopin specialist is a very special thing, an honour, but I love so many different composers and, being a big music lover, I wanted to explore many different repertoires. So I think in the 2018–19 season I intentionally avoided programming Chopin’s music in my recitals.”

This season, he’ll return to Chopin with the Second Piano Concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra and Gianandrea Noseda (they recorded it together in 2021) as part of Seong-Jin Cho’s Artist Portrait series with the LSO. In November, Cho will give the world premiere of Donghoon Shin’s Piano Concerto. Cho has literally just received the score of the first movement, which is parked on the Steinway next to which we are perched.

What were his first thoughts? Cho smiles. “Difficult!” Was he involved collaboratively in the compositional process? “Donghoon and I are good friends, so we communicate a lot about music, but I didn’t ask him anything specific. I just told him what I like and what I don't like about music in general. Looking through it, there’s no part that I don’t like, but it’s just… difficult!”

The LSO series will also offer Cho the chance to programme and perform recitals, both solo and with chamber ensemble, including members of the LSO in Brahms’ First Piano Quartet, a composer who appeals to Cho very much. “I’ve played the Clarinet Trio and the First Clarinet Sonata with Andreas Ottensamer. Whenever I play Brahms, I always imagine this warm horn and clarinet sound. It has ‘belly’! I love that kind of warmth. One of my favourite Brahms works is the First Violin Sonata. It feels like Brahms is embracing you from that first chord, so I really want to play this music in the future.”

Seong-Jin Cho performs Ravel with Semyon Bychkov in the Czech Philharmonic’s season opener on 25th & 26th September.

The Czech Philharmonic tour Taiwan and Japan from from 15th–22nd October.

This article was sponsored by the Czech Philharmonic.