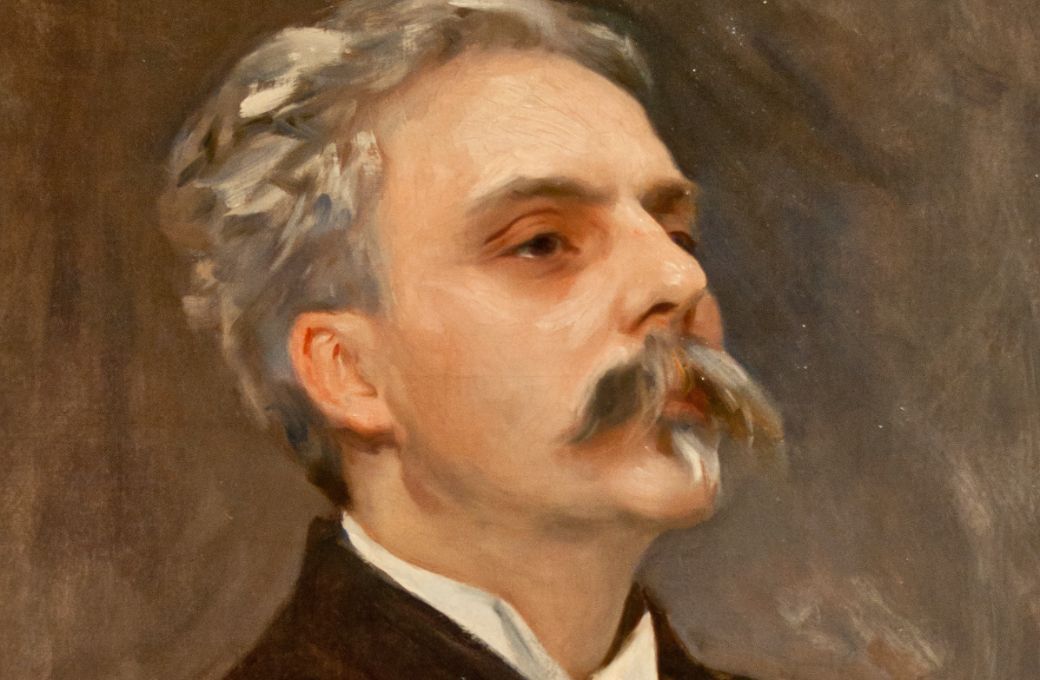

“When I am no more, you will hear said of my work: ‘After all, it is only so much…’ I have done what I could… and so, judge, my God.” The final words of Gabriel Fauré, as quoted in Marguerite Long’s book At the Piano with Gabriel Fauré, were typically modest. After pianist Robert Lortat gave a sparsely-attended recital of his music in 1914, Fauré consoled him with the words, “I’m not in the habit of attracting crowds.”

Today, Fauré is often obscured by the twin shadows of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel, perhaps because his music didn’t hide behind descriptive or evocative titles (La Cathédrale engloutie, Pavane pour une infante défunte). His originality is contained within outwardly traditional forms. Critic Émile Vuillermoz wrote that “Fauré is pure music… Under its apparent classicism, it contains the most magnificently revolutionary audacities.” This is particularly true of his profound yet luminous late music, with its daring harmonic progressions, which was written – just like Beethoven – when the composer had gone completely deaf.

Fauré was born on 12th May 1845 in Pamiers, a village in south-western France, the youngest of six children. “I grew up a rather quiet, well-behaved child, in an area of great beauty. But the only thing I remember really clearly is the harmonium in that little chapel. Every time I could get away I ran there – and I regaled myself. I played atrociously... no method at all, quite without technique, but I do remember that I was happy.”

After showing early talent, Swiss composer Louis Niedermeyer accepted him as a pupil in Paris, where he later studied piano with Camille Saint-Saëns, who took on the role of a father figure. At the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Fauré saw military action to raise the Siege of Paris and was awarded the Croix de Guerre. Fauré was an excellent organist – said to be a fine improviser – and was eventually appointed organist at the Église de la Madeleine. In 1905, he succeeded Théodore Dubois as director of the Paris Conservatoire, where his reforms earned him the nickname “Robespierre”. His pupils included Ravel, Enescu and Nadia Boulanger.

Although he composed some orchestral music and even an opera, Fauré excelled at music on a smaller scale – piano music, songs, chamber music; even his Requiem is quite intimate in nature.

1Requiem, Op.48

“It has been said that my Requiem does not express the fear of death and someone has called it a lullaby of death. But it is thus that I see death: as a happy deliverance, an aspiration towards happiness above, rather than as a painful experience.” In contrast to the barnstorming, earthquaking Requiems by Berlioz and Verdi, Fauré’s is much gentler, full of the consolatory feeling of faith in eternal rest. It exists in different versions from chamber orchestra to full orchestra. The closing In paradisum is, well, heavenly.

2String Quartet in E minor, Op.121

“I’ve started a quartet for strings, without piano. It’s a medium in which Beethoven was particularly active, which is enough to give all those people who are not Beethoven the jitters!” Like Beethoven, Fauré was completely deaf and in declining health by the time he composed his final work, a string quartet, finishing it just a few months before his death. Fauré’s late style is more abstract than before, the tonality more occluded. The sublime Andante is bathed in autumnal light, the finale like a Scherzo in disguise, reaching a jubilant conclusion.

3Piano Trio in D minor, Op.120

Fauré retired from his position at the Conservatoire in 1920, giving him more time to compose. He began writing his serene Piano Trio at his favourite resort of Annecy-le-Vieux in August 1922, although he was suffering from “perpetual fatigue”. He originally conceived it for clarinet, cello and piano, but switched the top line to violin. There’s a misty, melancholy quality to the first two movements – the Andantino has a wistful, songlike feel – but the finale dances, with surprising sudden twists and turns.

4Pavane in F sharp minor, Op.50

One of Fauré’s best known works, the Pavane nods towards the stately Renaissance dance, pizzicato strings hinting at a lute or guitar accompaniment. It was composed for small orchestra in 1886, shortly before Fauré wrote his Requiem, but it also exists in version with optional chorus (singing about dalliances between nymphs and shepherds) or as a work for solo piano.

5Piano Quartet no. 1 in C minor, Op.15

Despite its turbulent C minor key signature, Fauré’s early piano quartet is full of gentle warmth and optimism, with a jaunty Scherzo middle movement. Composition didn’t come easily though. Fauré began it in 1876 while he was in a relationship with Marianne Viardot (daughter of Pauline Viardot). Their 1877 engagement lasted barely four months, after which Fauré took another two years to complete the quartet, which finally premiered at the Société Nationale de Musique in Paris in 1880.

6Pelléas et Mélisande, Op.80

Maurice Maeterlinck’s symbolist play Pelléas et Mélisande was given modernist musical treatments by Debussy, Schoenberg and Sibelius, but the first composer to set it was Fauré, commissioned by Mrs Patrick Campbell to write incidental music at great speed for the play’s London premiere at the Prince of Wales’ Theatre in 1898. In the suite, Fileuse depicts Mélisande at her spinning wheel, while the airy Sicilienne is a gift for flautists. I find the autumnal melancholy of opening Prélude desperately sad, music later used by George Balanchine to open his ballet Emeralds.

7Après un rêve, Op.7 no.1

Fauré was a songwriter of great poise and sensitivity, writing over a hundred mélodies throughout his career. There are a couple of cycles – La Bonne Chanson and L’Horizon chimérique – but perhaps his most famous single song is Après un rêve, a dreamy, languid early work, published in 1878. It is based on a French adaptation of an anonymous Italian text describing a dream of a lover’s romantic rendezvous, but the dreamer awakes, longing to return to the mysterious night.

8Barcarolle no. 1 in A minor, Op.26

Fauré wrote a lot of music for solo piano, including sets of nocturnes, barcarolle and impromptus. A barcarolle is a Venetian gondola song, usually in a rocking 6/8 time. Fauré’s First Barcarolle, Op.26, is typically lilting, with a middle section featuring cross-rhythms and cascades of arpeggios. It was first performed by Camille Saint-Saëns.

9Piano Quintet no. 2 in C minor, Op.115

The Second Piano Quintet was a late work, composed in the greatest secrecy between 1919 and 1921. Fauré was increasingly deaf and composition was a slow, painstaking process. Writing in Le Temps, critic Émile Vuillermoz praised the work highly: “The Quintet in C has the paradoxical merit of bringing together two generally incompatible virtues: youth and serenity.” The key is constantly elusive in the quicksilver Scherzo, marked Allegro vivo, Fauré’s biographer Roger Nichols describing it as one of his “most astonishing inventions, pushing tonality as far as he would ever take it.”

10Cello sonata no. 2 in G minor, Op.117

Another late work in his pared-down style, the Second Cello Sonata was composed between March and November 1921. Early in the year, Fauré had received a state commission to write a work for a ceremony to be held at Les Invalides to mark the 100th anniversary of the death of Napoleon. Fauré duly complied but the resulting Chant funéraire seemed to stick in its composer’s head, re-emerging in Andante of his sonata, harmonised in a more enigmatic vein. The finale features a syncopated, almost jazzy melody. After the premiere, Vincent d’Indy wrote to Fauré to congratulate him: “The Andante is a masterpiece of sensitivity and expression and I love the finale, so perky and delightful… How lucky you are to stay young like that!” Here it is played by Fauré’s great champion of today, Steven Isserlis.