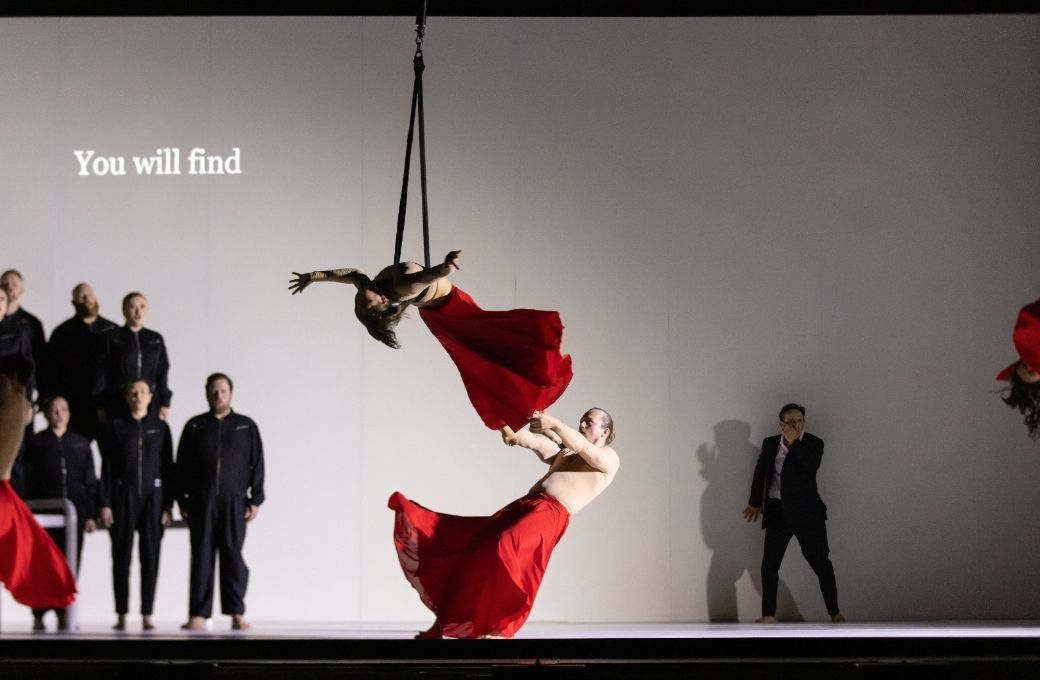

The overture is played curtain up, with a central stage column the only illuminated section. Suspended on high is an acrobat, a woman in a red dress, who descends slowly while entwining in and around the strap that holds her. The suggestion is of one falling, yet resisting. Eurydice, who has only just married Orpheus but then died, is descending to the Underworld.

Orpheus, in this Opera Queensland production of Gluck’s 1762 Orfeo ed Euridice, awakes in an asylum. Broken by grief, the events of the opera all take place in his deranged mind. One has learned to quail before the ‘promise’ of a “re-imagined” or “re-envisaged” treatment of a central repertoire opera, and this trope is not new, for it gives the director great scope. What could not be invented and passed simply as proceeding, like Macbeth’s dagger, “from the heat-oppressed brain”? The question arises, what has the director and set designer – Yaron Lifschitz – brought to it that is different and enlightening?

Lifschitz is the Artistic Director of Circa, the circus company which has often turned to opera for its productions, and Baroque opera has the appeal of numerous passages of ballet, giving space for non-vocal stage activity. So acrobatic spectacle is here not so much an addition to Gluck’s work, as a collaboration with it. Or even a usurpation of it for the unimpressed, for the whole of Gluck’s work, not just the third of it requiring ballet, features Circa’s contribution: aerial, grounded, tumbling, interacting with one another and with the singers. Bridie Hooper’s choreography certainly does not lack invention. Standing on each other’s shoulders we see human towers of three acrobats, tumbling forwards (cue gasps from the audience), seemingly imperilled but of course landing skilfully at the last minute. What is going in the opera at that moment becomes secondary.

So not all of this activity has the effectiveness of Eurydice falling into Hades during the overture. Some of it does, but acrobats, like those falling threesomes, offer a different kind of tension and resolution to that of words and music. As Lifschitz himself says “it’s a business based in danger”. For him the “core of theatre is ritual and rhythm, not story”. The success with the audience was not in doubt, for they accorded what they had witnessed the now familiar whoops and roars of people who have been so greatly entertained they must leap to their feet. All 3000 of them, for this production has been so admired around the world that perhaps only Edinburgh’s huge Playhouse could accommodate the demand. The operatic score seemed at times to play second fiddle, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and Chorus under Laurence Cummings swallowed up in the large auditorium and substantial pit.

But the singers coped admirably. The superb Samantha Clarke sang both Amore and Eurydice, with exquisite vocal allure, but confusingly to anyone coming new to this score, unaware that there are two separate characters. She was attired in red throughout as were the female acrobats much of the time, who at some points became additional Eurydices, each in turn blindfolded by Orpheus, who then glanced at, and thus slayed, each one. The heat-oppressed brain indeed. The set was austere, little more than the table-bed that Orpheus occupies at the start, and a small greenhouse, initially Eurydice’s tomb, later the venue for a “let’s see if we can squeeze in all the chorus” bit of fun. But it allowed space for the surtitles, for once easily visible without taking one’s eyes from the stage.

The opera is carried by Orpheus, who has little respite. Iestyn Davies’ countertenor was as plangent as ever, in what for him is a signature role. It is not a dramatic assumption, for all the lamentation that he must express. But as he notes himself, the role is quite different from many Baroque opera heroes, being focused on the beauty of the voice. He is Orpheus after all, and the Furies are quelled by the very sound of his voice, not by any dramatic threat he brings. Often we hear just him and the chorus, and it was difficult to resist the feeling that Gluck, in this revolutionary work aiming at a greater simplicity and musical directness in opera, would have loved the purity of such a presentation. Especially if he heard it in a venue of suitable scale.