“First they’ll have to know what a Peri is!” laughs conductor Laurence Equilbey, when I ask what anyone seeing Robert Schumann’s Paradise and the Peri for the first time should be on the lookout for. You’d be forgiven for not being able to identify the ancient-world’s least flashily-named superhuman: there has never been an I-Spy book of the Persian supernatural. You’d also be forgiven for having thus far missed the secular oratorio that turbo-charged Schumann’s international reputation in his lifetime; Simon Rattle has called it “the greatest masterpiece you’ve never heard of”.

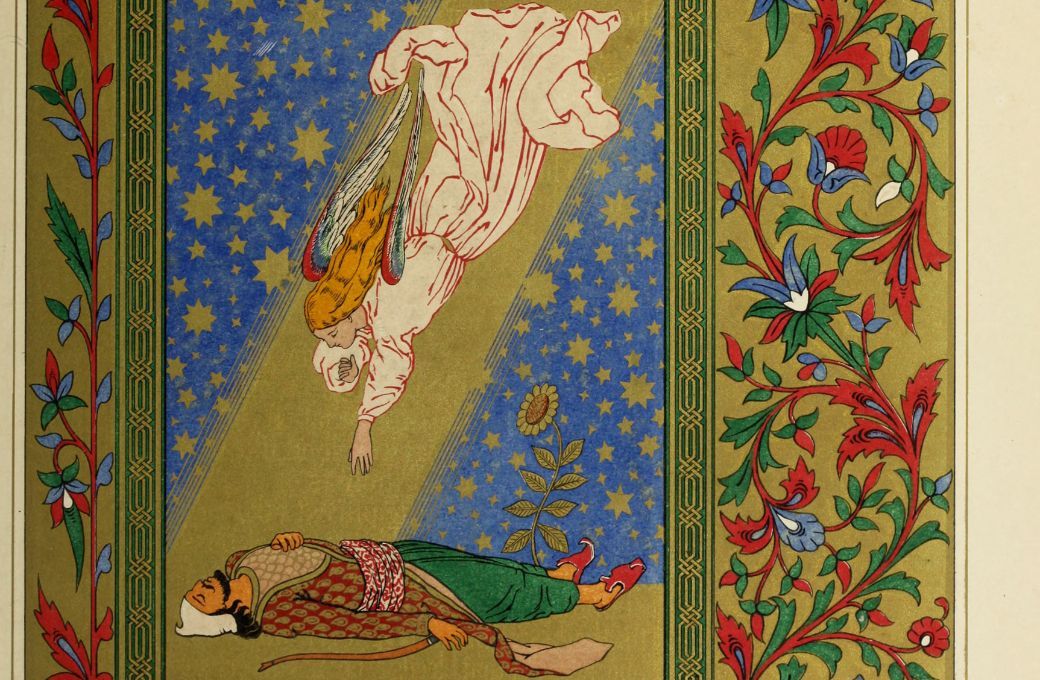

Let’s start with that Peri. “In Persian mythology,” explains Equilbey, “Peris are often described as a winged creatures of light and beauty, and they inhabit an intermediate space between the celestial and the earthly realms, symbolising the spiritual quest and the ideal of redemption. It is important to understand this from the start in order to fully immerse oneself in the story of this Peri, who seeks to have the gates of Paradise opened to her.”

We are all feeling rather cast out from paradise the day we meet by video call. Equilbey’s in Paris, director Daniela Kerck’s in Vienna and I’m in Lewes, but our weather is all the same – grey and cold, and two out of three of us have the flu. Between the coughing and sneezing we’re doing our best to envisage the arrival, in May, of “Schumann as you have never seen him” (so the publicity goes). The production is due to be staged in May at La Seine Musicale – the spectacular Shigeru-Ban-designed venue that rises like a celestial orb from the Île Seguin in Paris’ western suburbs. Glittering (when the sun’s out) on the site of the old Renault factory, La Seine Musicale is home to Equilbey’s resident Insula orchestra, whose speciality is bringing historically accurate performances of Baroque and pre-Romantic music to diverse, contemporary audiences.

Paradise and the Peri is based on one of the four stories in the 1817 Orientalist romance epic Lalla Rookh by Irish poet Thomas Moore, who had taken Byron’s advice to “look east”. To enter Paradise, the poor Peri in question must bring a gift to inspire forgiveness, for which she must travel to the ends of the Earth via, for example, the Isles of Perfume, the Vale of Rosetta, non-specific spicy bowers, the Tyrant of Gazna and his bloodhounds, and even the bees of Palestine. After much searching – and some truly eye-stretching encounters – the Peri collects the single tear of a repentant sinner and voilà, she’s in. The publishing sensation of its day (Longman advanced an unheard-of £3,000 – about a quarter of a million today), Moore’s poem lodged so indelibly in the popular consciousness that a century after publication even James Joyce’s fictional everyman, Leopold Bloom, imagined himself denied access to a better realm when a passing tram prevents him from catching a long-awaited glimpse of a woman’s underwear.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Robert Schumann saw something in the story of a questing soul on the brink of beyond that was to prove a breakthrough. Equilbey explains: “It is an important work that emerges at a crucial moment in Schumann’s career. He began composing in, I think, 1841 – at a time when he was trying to redefine his role as a composer, just as he was gaining increasing public recognition. He invested in large forms for orchestra, choir and soloists, but intended it for the concert hall, with the clear goal of preparing himself for even greater ambition: composing an opera in German. This work therefore marks the opening of a new perspective, and Schumann was very, very satisfied with it, to the point of considering it his greatest achievement.” Clara Schumann agreed, writing that it seemed to her the most magnificent thing he had ever written.

Schumann had created, says Equilbey, an innovative form, “one which drew the attention of Wagner, with its continuous musical fabric that breaks away from traditional distinction between arias and recitatives, as well as from the segmentation into independent numbers. He liked to say it was an oratorio for happy people, not religious ones. A secular oratorio imbued with spirituality and humanism.”

Similar in construction to a Bach Passion, with narrators and characters making a distinction between plot told and plot staged, this exotic extravaganza presents an irresistible challenge to director Daniela Kerck and her collaborator, video artist Astrid Steiner. Together they already created the extraordinary immersive visual experience that was Søren Nils Eichberg’s Oryx and Crake for Hessisches Staatstheater Wiesbaden in 2023. Steiner’s video art lends a visibility cloak to the metaphysical, creating another dimension on stage.

“We can’t illustrate the storytelling that’s already being sung,” Kerck explains. “You have to find stories in between.” Rehearsals were not yet underway when we spoke, but some crucial decisions had been made. Part of the set will be a giant LED wall, “a sort of magic box, a box where things are going to happen,” says Kerck, “that will be an integral part of the storyline. It’s amazing to have the opportunity to direct this piece. Anything is possible.”

The score, however, is more firmly rooted in early 19th-century Europe, as Equilbey explains. “Yes, of course I am a fan of historical instruments because I studied in Vienna for two years with Nikolaus Harnoncourt. Choosing period instruments means striving to get as close as possible to the sounds the composer had in mind and the sonic world of the time in which the works were created.

“Orchestral balances are deeply connected to the instrument-making of the era and also sometimes to the uneven timbres of the instruments and to their limitations, but also, and perhaps most importantly, to their poetry and their rich, subtle colours. The blend of woodwinds is remarkably homogeneous when using 19th-century instruments. As for the natural brass, which Schumann employs alongside chromatic instruments closer to modern brass instruments, their pitch is modulated by breath control and lip tension. Sometimes a wind section can resemble an organ.”

Developments in wind instrument technology around the time Schumann was writing Paradise and the Peri mean that this specific sonority evokes a strong sense of music at the threshold of the new. Similarly, the design and costumes, says Kerck, will embody “a timeless and poetic approach, that draws its inspiration from the Romantic era,” but will allow audiences to connect to the spirit of the age with a contemporary sensibility.

Although we now look at Romantic-era Orientalism through a post-colonial lens, we are – it would seem – living once more at a time when, perhaps aghast at reality, we want to be overwhelmed by our imaginations. I mention that my university students are obsessed with fantasy narratives and that redemptive quests in elaborately constructed other worlds form their natural habitat. “I think Schumann’s treatment of the theme of Orientalism is quite unique,” says Equilbey. “It’s not so much about exoticism as it is about seeking in a distant elsewhere the very roots of the human soul.”

Insula orchestra perform Schumann’s Paradise and the Peri at La Seine Musicale from 14th–17th May and at Vienna Musikverein on 30th May.

This article was sponsored by Insula orchestra / Accentus.