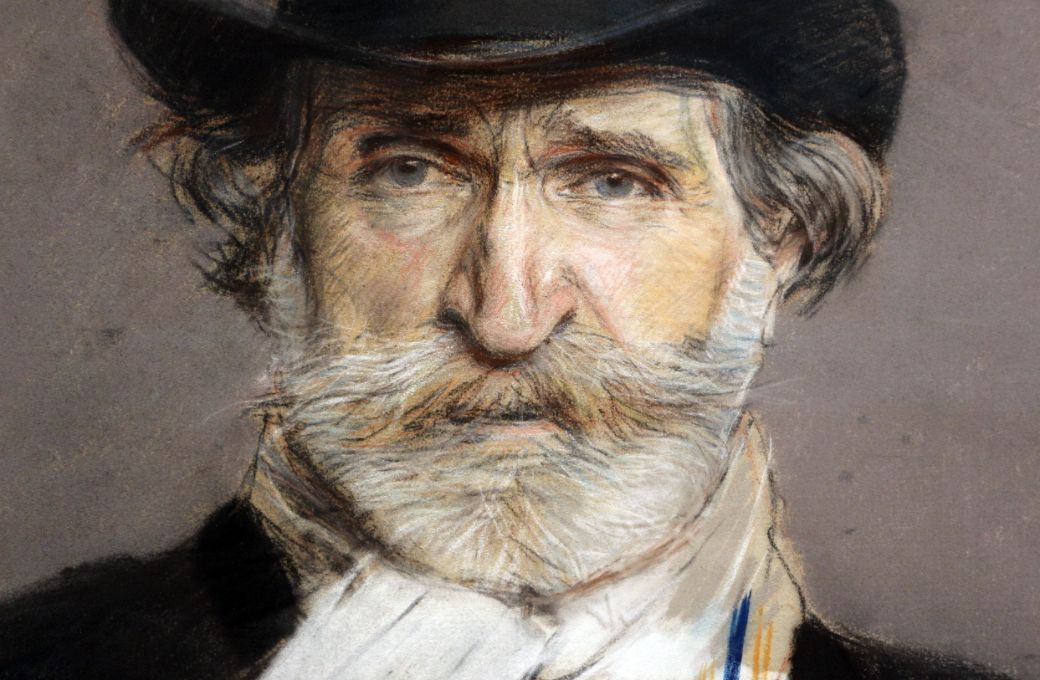

Of all the 19th-century Italian opera composers, one stood head and shoulders above the rest. But Giuseppe Verdi was more than just an opera composer. He became a political figurehead. His works were used as a rallying cry for the Risorgimento, the Italian unification movement, to the extent that at the 1859 premiere of Un ballo in maschera in Rome, the words “Viva VERDI!” were scrawled onto the walls of the Teatro Apollo, standing for Vittorio Emanuele Re d'Italia, who in 1861 became the first king of an independent, united Italy since the 6th century. Verdi himself briefly became a politician, entering the Chamber of Deputies once Italy was unified.

Verdi came from classic “humble beginnings”. He was born in the tiny village of Le Roncole, near Busseto in the province of Parma, in October 1813. As a child, he served as an altar boy in the local church, where he also learned to play the organ, becoming the official organist at the age of just eight. He attended school in Busseto, where he took music lessons with a co-director of the Philharmonic Society, composing marches, serenades and church music. He impressed Antonio Barezzi, the other co-director, and Verdi began teaching his daughter, Margherita, whom he married in 1836. Both their children died in infancy.

Verdi was refused entry to the Milan Conservatory, but was taught privately and succeeded in pitching his first opera, Oberto, to be performed at the illustrious Teatro alla Scala. While working on his second opera, Margherita died. Un giorno di regno, a comedy, flopped. Verdi was at his lowest ebb. Salvation came in the form of Nabucco, the tale of the biblical king Nebuchadnezzar. “Va, pensiero”, the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, particularly struck a chord with a Milanese audience under Habsburg rule. Verdi had his big breakthrough.

There followed what Verdi called his “Galley Years”, slaving away, writing two operas a year to secure enough of a financial footing to purchase land at Sant’Agata, close to Le Roncole, where he planned to live out his retirement. Giuseppina Strepponi, who had created the role of Abigaille in Nabucco, became Verdi’s second wife. A trilogy of great operas from 1851-53 – Rigoletto, Il trovatore, La traviata – secured Verdi’s place in the pantheon of opera composers.

With Les Vêpres siciliennes, Verdi tried his hand at writing grand opéra for Paris, thus challenging Meyerbeer in his own backyard. Operas such as Aida (Cairo) and La forza del destino (St Petersburg) saw Verdi in demand around the world. Life on the farm at Sant’Agata beckoned but his publisher, Giulio Ricordi, coaxed Verdi out of retirement, introducing him to a young composer and librettist, Arrigo Boito. Together, they revised Simon Boccanegra before embarking on two late masterpieces, both drawn from Shakespeare: Otello and Falstaff.

1Don Carlos

Originally composed in French (in five acts) for the Paris Opéra (later revised in Italian), Don Carlos is a prime example of what Verdi did best – juxtaposing the personal against the political – here with the backdrop of 16th-century Spain under the rule of Philip II. Based on Schiller, Don Carlos deals with huge themes of freedom and oppression, on top of which lies the doomed love of Don Carlos for Elisabeth de Valois, originally his fiancée but taken as a bride, for political reasons, by his father, Philip II. Throw in a jealous princess, a freedom-fighting bestie and the Spanish Inquisition and you have all the ingredients for an epic night at the opera. (In French or Italian, five acts or four, I still adore it.)

2Otello

Verdi was tempted out of retirement to compose Otello, a perfect operatic adaptation of Shakespeare, cutting the Venetian act and setting the entire work in Cyprus. From Otello’s trumpeted “Esultate!” entrance, the title role, written for Francesco Tamagno, makes huge demands on the tenor. Although Boito, the librettist, stuck closely to Shakespeare, he added a brilliant soliloquy for Iago, a Credo where he reveals his nihilistic beliefs, before sowing the seeds of destruction in Otello’s mind. In the 1980s and 90s, few performed the title role as brilliantly as Plácido Domingo.

3La traviata

La traviata was scandalous in its day, not least because it was a contemporary story based on La Dame aux camélias (1852), a play by Alexandre Dumas fils, adapted from his own novel which, in turn, was based on his relationship with Parisian courtesan Marie Duplessis. The premiere at Venice’s La Fenice was a flop, with the audience jeering the casting of soprano Fanny Salvini-Donatelli as Violetta, seen as too old and overweight to play a young woman dying of consumption. “La traviata last night was a failure,” wrote Verdi. “Was the fault mine or the singers’? Time will tell.” Traviata is now one of the most performed operas in the world, a popular vehicle for star sopranos singing the role of Violetta, who renounces her love for Alfredo to save his family's honour.

4Aida

Aida is the quintessential “grand opera”, usually associated with parading elephants and epic sets evoking Egyptian splendour. In truth, you’re unlikely to see elephants now, even at the Arena di Verona, and spectacle is usually at a premium in all but the glossiest productions. Behind the famous Grand March, however, is an intimate love triangle, where jealousy and patriotism intervene, resulting in Egyptian warrior Radamès betraying his country, sentenced to be buried alive. His lover Aida, the Ethiopian slave who is, in reality, a princess, joins him in the tomb.

5Rigoletto

Verdi also ran into problems with the censors with Rigoletto, his operatic take on Victor Hugo’s Le roi s’amuse. It was considered improper to portray a king (Francis I of France) as a licentious womaniser, so he was turned into a Duke of Mantua. Verdi’s depiction of the title role, a hunchbacked jester who is shielding his daughter from the public eye, is masterly, showing both a vicious tongue as the Duke’s sidekick and paternal care that turns to anguish when his daughter, Gilda, sacrifices herself for the Duke, fulfilling the curse laid on Rigoletto in Act 1.

6Il trovatore

Often parodied for its convoluted plot (essentially it boils down to the daughter of a condemned gypsy throwing the “wrong” baby into the fire and two men, rivals for the hand of Leonora, not realising they are brothers until it’s too late), Il trovatore is crammed full with great music. Directors struggle to take the plot seriously, so it’s rarely staged these days, but it’s also tough to find singers up to the challenge. The famous tenor Enrico Caruso once remarked that all it takes for a successful performance of Trovatore is “the four greatest singers in the world” and he’s not far wrong.

7Nabucco

Verdi’s breakthrough opera is notable for its great choral writing. In Act 3, the Hebrew slaves, on the banks of the Euphrates, long for their homeland. Verdi later told the story about how he had to be persuaded to take on the La Scala commission. The impresario had given him a copy of the libretto, which Verdi took home and flung on the table “with an almost violent gesture… In falling, it had opened of itself; without my realising it, my eyes clung to the open page and to one special line: ‘Va, pensiero, sull'ali dorate’, (Fly, thought, on golden wings)”, which became one of opera’s most beloved chorus (and almost a national anthem for Italians).

8Messa da Requiem

Not an opera, but inherently operatic, Verdi’s Requiem was composed in memory of the poet and novelist Allesandro Manzoni. The Dies irae, evoking the Last Judgment, is full of blood and thunder – and a gigantic bass drum – and there are deeply personal parts for the four soloists, culminating in the soprano’s impassioned Libera me. The conductor Hans von Bülow criticised Verdi’s Requiem as “an opera in ecclesiastical garb”, but it’s these very dramatic qualities which have made it one of the most performed religious works in the entire choral repertoire.

9La forza del destino

Like Trovatore, Verdi's The Force of Destiny is another opera with its fair share of incredulous events and unlikely coincidences, from the moment Don Alvaro – Leonora’s unsuitable suitor – accidentally shoots her father dead in Act 1, setting in trail a long opera of vengeance and bloodshed. At one point, Alvaro and Carlo (Leonora’s brother) are both on stage in disguise, the one saving the other’s life without realising that he’s really the enemy he’s been pursuing. In the end, Alvaro slays Carlo in a duel, but not before Carlo stabs his sister, who has been living as a religious hermit. That’s fate for you.

10Falstaff

We had to end with something a bit more light-hearted. Falstaff is Verdi’s autumnal comedy in which the great knight – great as in “large” – gets his comeuppance for wooing the Merry Wives of Windsor in order to get his hands on their purse-strings. Verdi hadn’t attempted a comedy for half a century – indeed, Rossini had thought him incapable of writing one. Falstaff is a comic masterpiece, full of brilliant ensembles, none finer than its finale. A comic fugue was an unpredictable way to bring down the curtain on Verdi’s operatic career, but it was an inspired choice. Fittingly the last two lines of the opera translate to: “But he who laughs the final laugh, laughs well.” With Falstaff, it was Verdi who had the last laugh.