Playing an instrument is reliant on the use of the hands and body – but there is something special too about the act of writing music by hand. “I’ve always had this absolutely ecstatic relation to hand notation: making a mark, and it’s like the mark comes alive,” says composer Liza Lim. “It’s speaking to me and it’s pushing back at me. I have this sensation that as much as I’m making the music, the music is making me.”

Lim, who earlier this month won the prestigious Grawemeyer Award for her cello concerto A Sutured World, is a keen advocate for music handwriting. As music technology changes, fewer composers and arrangers are writing music by hand, with increasing reliance on computer notation for convenience and portability. Yet until relatively recently, the act of sketching and drafting by hand was essential to composition. It is an activity that draws together line, weight, proportion, curve, flow, the arc and the straight edge. Harmonies crowd and pile upon one another. One comes to hear the music through one’s hand.

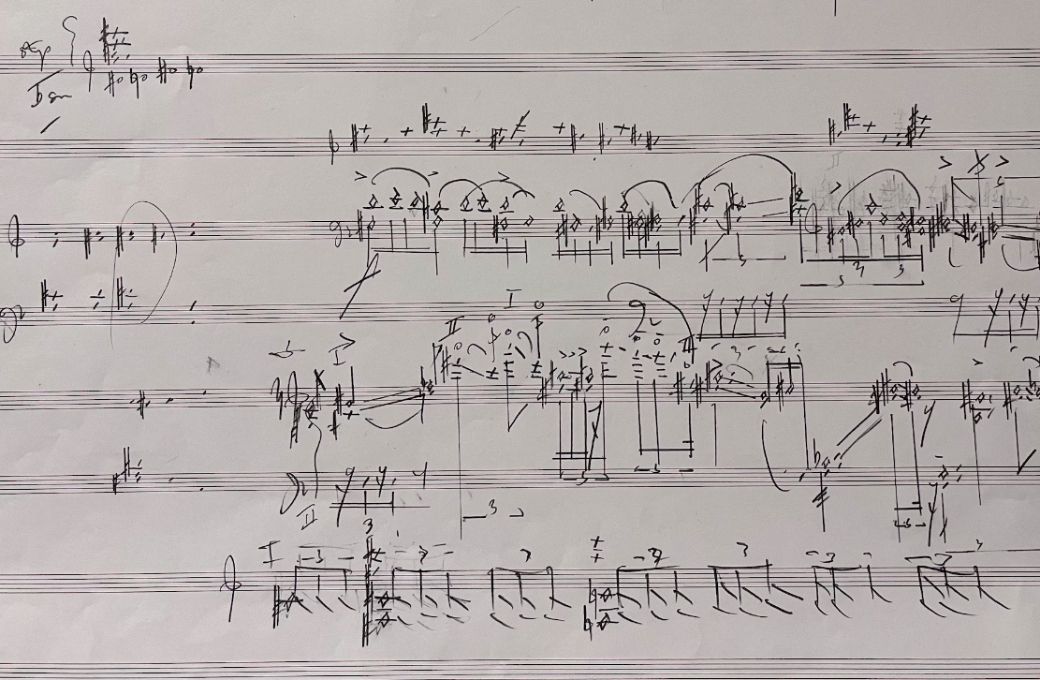

“It’s a very rich sensory activity – and the hand-eye coordination puts you in a flow state,” Lim says. She shares with me a sketch from the concerto: on the one side are some harmonies, destined for the orchestral ensemble, while on the other side are notations for the solo cello. Harmonics bounce and slide between staves, or cascade in semiquavers. Erased lines appear in ghostly form in the background. Repeated glissandi in triplets smear and smudge.

With the increasing digitisation of manuscripts, it’s possible to see composers’ handwriting from across music history, something previously only available to researchers and specialists. Through their hands, it’s possible to feel the presence of the composer directly – as Lim says, in the handwriting is “embodied knowledge, musical thought: sound and kinetic flow appear with immediacy”.

Early notations

Most early music notation that survives is written by scribes, but there are places where we can sense the presence of the composer’s hand. Baude Cordier’s canonic composition “Tout par compas suy composes” (“With a compass was I composed”) is surely one, written in a circle, with two separate ink colours indicating metrical proportions. If this neat copy is not by the composer themselves, it must have been designed by the composer for a gifted scribe. Virtually nothing is known about Cordier besides these surviving manuscript pieces in the Chantilly Codex, dating to around 1400.

Another manuscript which may preserve its composer’s hand is Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Lamentations of Jeremiah, written at the end of the 1500s. Cavalieri was one of the most advanced and adventurous musicians of his era, combining the expressive madrigal style with newly forming basso continuo monody, a style dubbed stile rappresentativo. (His work Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo uses this style and may be the first oratorio or opera.)

Cavalieri’s Lamentations are preserved in a manuscript in the Biblioteca Vallicelliana in Rome, and contain arguably the earliest surviving notation for basso continuo. The handwriting is quick, cursory, spilling over into extra bars at the end of lines, with alternative passages, abbreviated sections, cancelled and corrected notes. The music, which alternates between polyphonic and monodic passages, is highly chromatic frequently very challenging to sing.

In one extraordinary passage, Cavalieri supplies three endings to a section of monody, two in his characteristic chromatic style, and a third using an ‘enharmonic’ division of the tone into five parts, with the singer’s line rising through these five micro-intervals. Only a custom-built organ, designed following the theoretical principles of visionary music theorist Vicentino (who Cavalieri knew) could have accompanied a singer in this passage.

Buxtehude, Bach and Handel

Dietrich Buxtehude’s cantata cycle Membra Jesu nostri, written in 1680, definitely preserves the composer’s hand – but here in an unusual tabulature form. This was the way organ music was commonly notated in North Germany, and organ tabulatures of various kinds had been used elsewhere for many years prior. However this manuscript is not (only) for organ, but for instruments and singers, and it was from this master score that the parts would have been made. Buxtehude would have composed directly into tabulature rather than needing to write an alternative notation first.

Rhythms are indicated above, with note names written with letters beneath. In the choral passages, all the instrumental and vocal parts are indicated in this way. Each of cycle’s seven cantatas is dedicated a different body part of the crucified Jesus: the feet, the knees, the hands, the sides, the breast, the heart, and the face.

Johann Sebastian Bach knew organ tabulature – and occassionally used it, sometimes as a way of saving space. These are amongst the many thousands of surviving pages of his striking music calligraphy in conventional notation. In contrast to the clarity of Italian penmanship of Cavalieri’s time, which does not make great distinction between heavy and light strokes, Bach (especially in later years) utilised a heavy contrast in his calligraphy, between thin vertical stems and flowing, dark beams.

Bach taught notation to all his children and pupils and one can see his influence in the many surviving manuscript parts made by his army of copyists. He also sometimes ate and drank at his desk while notating, and some manuscripts preserve grease stains along with fingerprints. The manuscript for the St Matthew Passion, a fine example of Bach’s calligraphy, also contains a circular stain from a drinking cup. Indeed, the manuscript had to be repaired, as its edges had been damaged by mice. A strip of paper had to be glued to the edge of each page, and Bach’s handwriting can be seen in two stages: the main bulk from the 1730s, with repairs made perhaps ten years later.

Another piece being written down at this time was Handel’s Messiah. Despite their being of the same generation, Handel’s handwriting differs considerably from Bach’s – even in earlier decades, it was plainer and less adorned. By the 1730s, it had become scratchy and uneven, with a visible diagonal slant: Handel had suffered a stroke in 1737, which affected the use of the right-hand side of his body.

Despite Handel’s physical problems, the manuscript for Messiah is not all that difficult to read, perhaps thanks to the straightforwardness and familiarity of the music. It’s also helped greatly by Handel’s rather naïve handwriting for the oratorio’s English text. In contrast, while Bach’s flowing German kurrentschrift was the standard at the time and well-understood by singers, reading it today poses significant problems even for native German speakers.

Pencils and pens

The popularisation of the pencil around the turn of the 19th century proved especially helpful for artists and musicians – the Koh-i-Noor Hardtmuth company, founded in 1790, patented the pencil lead in 1802, and its stationary remains popular with musicians today. Annotations could be made and erased, and rehearsals became easier. It was around this time that the rehearsal mark also developed.

The manuscript to Robert Schumann’s First Symphony, written January to February 1841, preserves the preliminary sketch Schumann made for virtually the entire work, proceeding movement by movement from start to finish. After the stately introduction, written first in pen, the brisk Allegro continues in pencil, with Schumann generally writing only the top line and occasional snatches of bass line and internal lines when needed. By the end of the development section, the structure is so obvious to Schumann he barely needs to notate anything apart from empty bars.

Unfortunately, the score itself doesn’t turn out quite as smoothly as Schumann had hoped. Above its delicate pen calligraphy it contains passages pasted on and added in pencil, and several alternate endings. Even despite this effort, the whole piece was revised over again, with a new manuscript being written by a copyist (it is this version that is performed today, and not the version in Schumann’s autograph).

Schumann’s hero Beethoven also heavily relied on his copyists. While Beethoven could sometimes neaten his handwriting, his symphonies are notorious for their messiness and scrawl, the Fifth especially. Reading it is a thrilling experience: Beethoven’s pen lashes against the paper furiously, the music struggling, like a wild animal the composer is wrestling to tame.

Other composers’ hands

While wild untidiness is still present in sketches, as the 20th century progressed, composers were generally required to become neater. Complexity of the music meant that lines and notes could not be so easily inferred from harmonic context. Later still, publishers began putting out facsimiles of the composer’s notations themselves, due to a reluctance to pay for engraving.

Here are some other examples of composers’ handwriting: