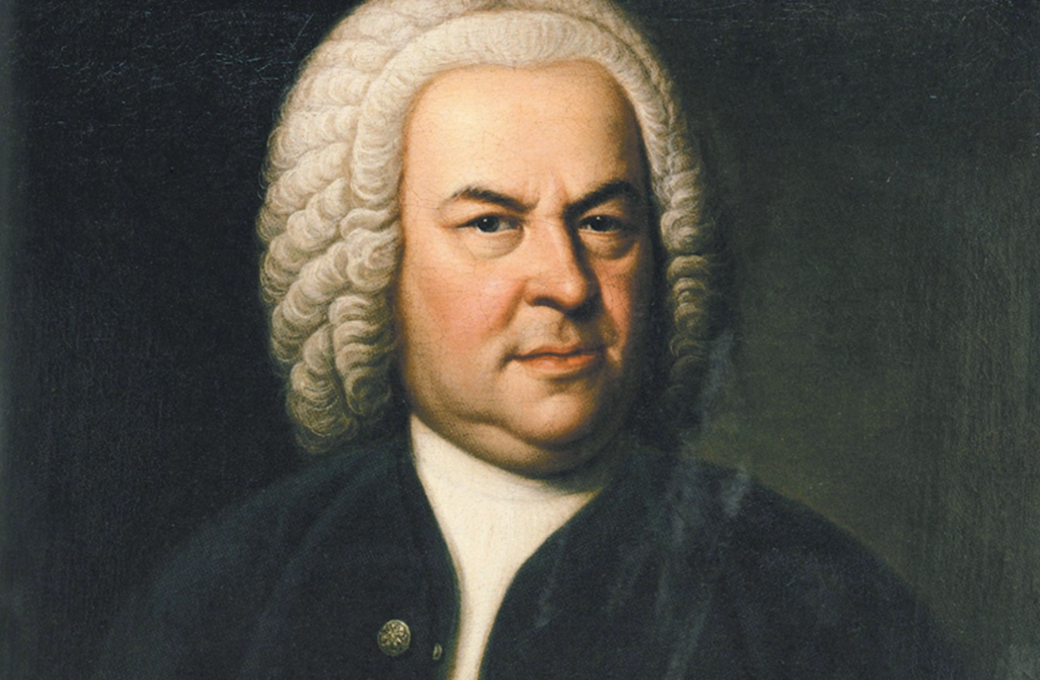

“I play the notes as they are written, but it is God who makes the music.” If Mozart and Beethoven are the Son and the Holy Ghost of classical music’s Holy Trinity, it is surely Johann Sebastian Bach who is the Father. Renowned for his harmonic invention (“Harmony is next to Godliness”) and contrapuntal techniques, Bach was a prolific composer, influencing the way music developed through the Baroque era and beyond.

Born into a musical family in 1685 – his father Johann Ambrosius was director of the town musicians in Eisenach – Johann Sebastian was perhaps always destined to be a composer (and he fathered many!). Orphaned at the age of ten, he moved in with his older brother Johann Christoph. In 1703, he became employed as the church organist in Arnstadt, from where he walked to Lübeck to hear Dietrich Buxtehude play the organ and to further his musical education – a journey of 450km!

Unlike his cosmopolitan contemporary Handel, Bach spent his entire life in Germany, filling roles as organist (Arnstadt, Mühlhausen and Weimar), Kapellmeister (Köthen) and finally Thomaskantor and music director of the city of Leipzig. During his time at Weimar, Bach began composing keyboard and orchestral works and studied the music of Italian composers, even transcribing some of Vivaldi’s works. From 1717, when he was hired as Kapellmeister in Köthen, Bach composed a lot of secular music, but it was the Leipzig appointment in 1723 that saw the composition of the bulk of his sacred music.

As director of church music in the city, Bach was responsible for composing the cantata that was required for the Sunday services and church holidays, most adopting texts from the gospel readings for that particular Sunday in the church calendar, adding Lutheran hymns for the congregation to join in. Bach wrote over 300 cantatas in his lifetime (around 100 of which have been lost), along with great sacred masterpieces such as the St Matthew and St John Passions, the Mass in B minor and the Christmas Oratorio.

But it wasn’t all church music in Leipzig. Bach also liked to frequent Zimmermann’s coffeehouse, where concerts were given free of charge and where many of Bach’s instrumental works were performed.

Bach died in 1750 after complications resulting from eye surgery to remove cataracts – ironically by the same charlatan (John Taylor) who later messed up Handel’s vision.

1Brandenburg Concertos, BWV1046-51

Bach composed his set of six concertos “for several instruments” and presented them to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg. Each is scored differently (trumpet in no.2, recorders in no.4), with no single soloist, although I love how the harpsichordist steals the limelight in a lengthy first movement cadenza in the Fifth. Vivid and inventive, this is music that never palls. I could easily fill six playlist spots with them… so I’m cheating and offering a video of Claudio Abbado conducting all six in one go!

2St Matthew Passion, BWV244

Even as a non-believer, there’s something I find incredibly moving – and humane – about Bach’s Passions, which narrate the final hours of Jesus’ life as remembered during Holy Week (the two parts were intended to flank a Good Friday sermon). The St Matthew, composed a few years after the St John, contains music of reflective and emotional power: chorales, double chorus and double orchestra, recitatives relayed by a tenor Evangelist and a bass Christ. The arias can be heart-stoppingly beautiful, none more so than the alto aria “Erbarme dich”.

3Double Violin Concerto in D minor, BWV1043

Bach composed two concertos for solo violin, but it’s the Double Concerto for two violins that is an audience favourite. It was probably composed around 1730 and premiered at the Friday night concerts in Zimmerman’s Coffee House. Expressively intense and full of character, the outer movements show the influence of Vivaldi’s zesty writing, although the counterpoint is very Bachian and all three movements are fugues, the two soloists repeating each other in concentric circles. In the sublime central Largo, Bach spins the most eloquent melody, passed between the two protagonists.

4Goldberg Variations, BWV988

Of Bach’s solo keyboard writing – including Preludes and Fugues in the 24 different keys which set the template for generations of composers to come – the Goldberg Variations particularly capture the imagination. Count Keyserling, a Russian ambassador to the Court of Saxony, suffered from insomnia and, the story goes, asked Bach to write some music for his chamber musician, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, to play to soothe him during his sleepless nights. The work takes a simple opening Aria and treats it to 30 sets of variations, those variations divided into two sections. The Polish harpsichordist Wanda Landowska described Variation 25 – a long Adagio – as the “Black Pearl" of the set. In a symmetrical move, Bach closes the work with a repeat of the opening Aria.

Should you play the Goldbergs on a modern piano or a harpsichord? It’s an age-old debate and not one for here... so why not enjoy both!

5Mass in B minor, BWV232

Completed a year before the composer’s death, the Mass in B minor had a long gestation, drawing on earlier compositions such as a Sanctus written in 1724. The opening Kyrie and Gloria date from 1733, when Bach presented it to the new Elector of Saxony, citing it as “a modest example of the learning I have acquired in music.” The work is shrouded in mystery, not least why the Lutheran Bach set the text of a Catholic mass to create a two-work of great dramatic sweep that would have been unlikely to have been performed in a Leipzig church service. The Mass is, in many ways, a summation of Bach’s brilliance, featuring outstanding examples of counterpoint, fugue and polyphony, mixing chorales with writing that nods to the secular styles of Italian and French opera.

The Mass was never performed during Bach’s lifetime. It was not published until 1845 and the first known performance took place in 1859.

6Chaconne from Violin Partita no. 2, BWV826

Bach’s writing for solo strings – three unaccompanied violin sonatas, three violin partitas, six cello suites – are the pinnacle of Baroque string writing. “He understood to perfection the possibilities of all stringed instruments,” Carl Philipp Emanual Bach wrote about his father. The first half of the Partita no. 2 contains four Baroque dances: Allemanda, Corrente, Sarabanda, Giga. But then comes an astonishing, profound Ciaccona (Chaconne), a lengthy set of variations over a repeating harmonic pattern, moving in 3/4 sarabande rhythm. “On one stave, for a small instrument,” Brahms wrote to Clara Schumann, “the man writes a whole world of the deepest thoughts and most powerful feelings.”

7Cello Suite no. 1 in G major, BWV1007

The “Old Testament” of the cello repertoire, Bach’s six suites hold a special place in the hearts of many cellists. They were composed during the period when Bach was serving as Kapellmeister in Köthen. After an elaborate opening prelude, there follows a succession of fast or stately dance movements. The First Suite is perhaps the best known, especially the Prelude with its series of arpeggiated chords.

8Ich habe genug, BWV82

One of Bach’s most popular cantatas, Ich habe genug (usually translated as “I am content”) was composed for the festival of the Purification of the Virgin Mary on 2nd February 1727. It is, unusually, a cantata for solo bass voice and contains no chorus or chorale, just three arias linked by recitatives. The text draws from the Gospel of Luke (Chapter 2, v 22-33) where the infant Jesus is presented in the temple and Simeon, an elderly man, recognises in him the promised Messiah and says: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: for mine eyes have seen thy salvation.” Resigned, melancholy, but poignant – and content. As Mark Swed described the cantata, it is “a manual for how to die sublimely, mapping the road to paradise”.

9Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV565

I wonder how many people’s introduction to Bach was through Leopold Stokowski’s lush orchestral transcription of the Toccata and Fugue in D minor that opens Disney’s animated classic Fantasia? It was certainly mine. But as colourful as Stokowski’s brushwork is, here’s Bach’s organ original.

10Orchestral Suite no. 2 in B minor, BWV1067

If the Brandenburgs represent Bach’s finest writing in the Italian concerto style, the four orchestral suites nod towards France. Bach called them “ouvertures”, referring to the opening movements with their dotted-note rhythms characteristic of the grave introductions to French Baroque music such as the overtures to operas written by Lully. The suites feature traditional French dances such as the Rondeau, the Bourée and the Menuet. The Second Suite has a prominent role for solo flute, closing with the famous Badinerie, a showstopper for the flautist.