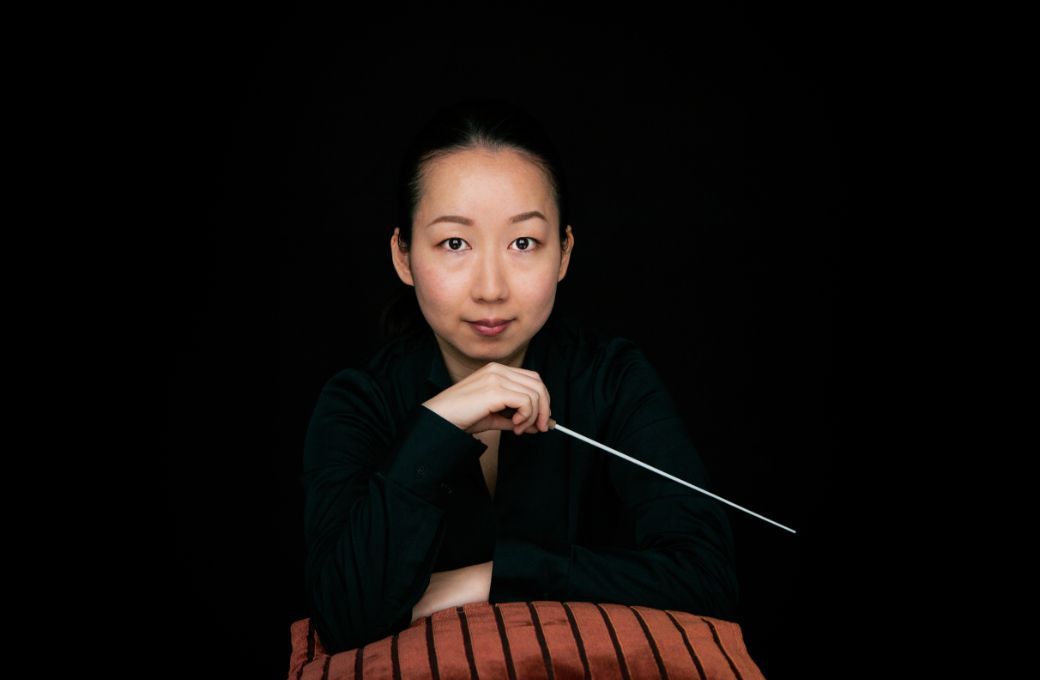

Brahms and Weber were showcased to impressive effect at the Anvil in the last stage of the Philharmonia’s mini concert tour, each of the four events featuring clarinettist Michael Collins. Replacing the originally advertised Marta Gardolińska, guest conductor Nodoka Okisawa made clear her credentials in a convincing partnership with the orchestra in three highly involving accounts. If she was an unknown quantity in the UK before this series, Okisawa proved to be a compelling force, notwithstanding her undemonstrative manner.

But there was considerable authority in the unfussy gestures that guided the Philharmonia through Weber’s overture to Der Freischütz. After a tentative start, a momentum-filled account unfolded combining dramatic bite and considerable joie de vivre in the conjuring of the peasants’ knees-up. There was some fine playing too, notably from mellifluous horns and woodwinds, Okisawa also coaxing polished string playing, the whole gloriously unbuttoned in the final furlong.

There followed a characterful performance of Weber’s idiomatically scored Clarinet Concerto no.1 in F minor, a work less frequently performed in concert halls today, but one that still manages to excite the ear on each hearing. Thanks to the sublime artistry of Michael Collins, this rendition was no exception. From the opening bars, Okisawa brought a wonderful clarity, a sense of intimacy as if imparting some hidden secret. Add to this dewy surface the deliquescence of Collins’ clarinet, we had absolute perfection. Phrases were begun with the softest murmurings, caressing and developing each with a musicality that combined an effortless technique and searching intelligence.

The Mozartian Adagio also found Collins in poetic mode, his traversal cementing an already flawless collaboration where balance and ensemble were nowhere better heard than in the imaginatively scored passage for solo clarinet and three horns. A rapt silence from the audience could provide no greater compliment to the playing. If the first two movements emphasise the clarinet’s lyrical properties, then the witty Rondo places agility centre-stage. Here, a nimble-fingered Collins made the most of Weber’s merrymaking, throwing caution to the wind in the final paragraph, completely at ease with a faster, seemingly homicidal tempo, with edge of seat excitement brilliantly served.

The darkness-to-light traversal that is Brahms’ First Symphony was also admirably served, and developed from a forthright, pugnacious opening movement, Okisawa underlining the score’s dark colouring and heroic ambition. Yet there was nothing routine in this performance, every phrase played with real feeling and affection. Warmth from the Philharmonia strings and persuasive solo contributions brought dividends to the Andante, but despite the atmospheric closing bars, serenity was in short supply.

The third movement’s grazioso sections never quite found enough charm and the central panel’s assertive rhythms brought some rhythmic uncertainty. A less experienced conductor might have lost their nerve at this point, but Okisawa put the incident behind her and went on to create a superbly paced Finale. The Philharmonia’s expressive power came to the fore, aided and abetted by a resplendent horn solo, Okisawa and the players ultimately vanquishing the terrors of Beethoven in the closing page’s affirmation of life. Whatever had gone before, this closing movement demonstrated a superb alliance between podium and players and demonstrated beyond doubt that Okisawa is a name to watch out for.